Regulation keeps them from being an iffy proposition

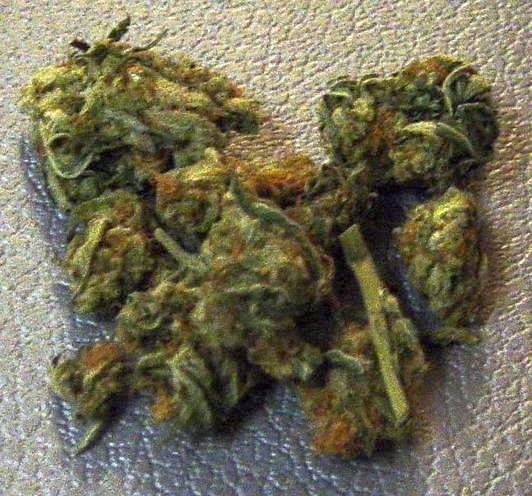

The recent death of a 19-year-old exchange student has led to a surge of concerns about the safety and regulation of edible products in Colorado. Levy Thamba of the Republic of Congo allegedly ate marijuana edibles in Denver during spring break with friends in March, then jumped from a hotel room balcony later that night. Thamba’s is the first death officially related to “marijuana intoxication” on a coroner’s report since Colorado legalized marijuana in January 2013.

While Thamba’s death is tragic, it is not a realistic indication of a larger public threat. Thamba’s friends also ate the edibles that night, and thousands if not millions of people eat marijuana edibles every day without issue. In California, hundreds of medical dispensaries have sold countless edible marijuana treats to sick people since the ’90s, and nothing like Thamba’s tragedy has been reported. In its coverage of Levy Thamba’s death, CBS Denver spoke with a doctor who reported that marijuana intakes in the emergency room are rare while alcohol-related intakes happen every day. Very little has been reported about other possible underlying factors in Thamba’s death, and medical professionals remain baffled by this incident because it is so far from the norm.

If anything, Thamba’s story proves the need for better drug education in the U.S. Many things about the incident remain unclear, including the amount of edibles Thamba consumed. It has been reported that that night was the first time Thamba ever used marijuana, and Thamba and his friends did not know the dosage of THC (the psychoactive part of the plant) they were consuming per edible because their edibles had not been tested.

Additionally, edibles take much longer to kick in than smoked marijuana and often people become impatient and assume they haven’t taken enough, then end up eating much more than they should. This often causes intense feelings of panic, which it sounds like Thamba may have experienced. Because of the way edibles are metabolized and absorbed in the body, their psychoactive effect is five times stronger than smoked marijuana, and on average edibles take one to two hours to kick in, about four hours to peak, and about eight hours to finish—but Thamba and his friends probably did not know this. It’s also possible Thamba and his friends were unaware that cannabis consumption alone cannot kill you, which may have lessened the overall panic. No one has ever overdosed on pot.

Alec Dixon of Santa Cruz, Calif. works at a cannabis testing lab called SC Labs, which tests cannabis samples for possible contaminants like pesticides and foodborne germs. Dixon also works as an educator for medical marijuana patients in the area, teaching them about safe ways to consume cannabis. One of the main things he tells people is not to consume edibles the first time they use marijuana, and if they must start out with edibles, to take it slow and make sure they know how much they’re taking.

“If you eat an edible you don’t know, unless it’s been tested by a lab, how many milligrams [of THC] are in it,” said Dixon. “Edibles are kind of tricky because your experience with cannabis—whether you’re new to it or you’ve been smoking for a long time—and your body weight—say a 200-pound man versus a 105-pound cancer patient—that plays a big role. That’s why it’s so important to know how many milligrams you’re taking.”

No Universal Standards

In most parts of the country, testing labs are still few and far between if they exist at all. Edibles are a popular, sometimes necessary, alternative for patients with serious illnesses or those who simply don’t want to breath smoke, and they generally taste good. But because the U.S. government still considers all things cannabis strictly illegal, there are no universal standards in place for edibles. Throughout the 20 states (and Washington D.C.) that have legalized marijuana for medical or recreational purposes, there are many different manufacturers working with many different strains and differing rates of quality, so it’s difficult to know how high you’re going to get from any given edible, and what the effects will be. There are no government regulations, no general labeling standards, and the federal agencies that normally oversee food safety aren’t testing marijuana food products for contaminants like mold, pesticides and foodborne illnesses.

In a recent effort to fill those gaps, Colorado recently added requirements to test for food contaminants in edibles, in addition to potency. The state’s Marijuana Enforcement Division enacted the new regulations in early March but testing has yet to be fully implemented, and according to an article in the Denver Post, many “labels” are inaccurate. The Post organized independent tests of THC levels for various treats within pot shops in the city, and the results were not promising. The Post reported, for example, that products from Dr. J’s Hash Infusion, one of the largest producers of marijuana-infused edibles in the state, only contained a “minute fraction” of the THC promised by its labels.

Once standardized testing labs are in place, it could change the game for edibles, which have been a media hot topic in recent months due to (usually overblown) fears surrounding dosage and food safety. In an article about Colorado’s new regulations, Lewis Koski, chief of the marijuana enforcement division told Salon that to a “large extent” the state is learning as it goes.

“The right thing to do, from a regulatory standpoint, is to make sure we can comprehensively regulate all these businesses and ensure the health and welfare of the citizens of Colorado,” he said.

So far, throughout most of the 20 states (plus D.C.) that allow medical marijuana, if any testing is happening, it’s happening via independent, privately owned labs. Dispensaries retain the option to opt in and order lab tests—or not.

Testing By Patient Demand

It wasn’t until six years ago that the first-ever cannabis testing lab in the nation opened its doors, not in Colorado but in Oakland, Calif.—a state where hundreds of hodgepodge of medical dispensaries still lack any state-standardized operational guidelines. That lab was Steep Hill Halent, and still offers cannabis testing services.

In the last six years, scores of testing labs have popped up across the Golden State. Alec Dixon partnered with the original laboratory director of Steep Hill to open up SC Labs four years ago. Today Dixon’s labs test about 5,000 cannabis samples a month for everything from microbes and pesticides to potency and cannabinoid profiling, which means actually mapping out the sometimes hundreds of different compounds that make up a single cannabis plant. SC Labs also does consulting for companies that make infused cannabis products.

While it has yet to legalize recreational weed, in many ways California has paved the way for the pot frontier. It was the first to allow medical marijuana when Prop. 215 passed in 1996. Cannabis cultural hubs dot its coast, from Venice to Humboldt and its medical marijuana program is also among the most accessible in the nation; patients with issues as benign as back pain or as serious as cancer can stop in to visit specified pot docs who will exchange medical cards for a small fee. But despite little official oversight, California’s dispensaries are somewhat self-regulating: as patients become more educated about cannabis safety, they’re choosing to get their buds and edibles at dispensaries that use testing labs. Since there enough labs in the state to make for real competition, that is incentive enough for most dispensaries to start testing.

“One of the real big focuses of our direction as a laboratory is educational forums and seminars and patient outreach seminars,” Dixon said. “Because, whenever education comes out what we have seen as whole in California is a patient-realized and patient-driven demand for tested medicine and consistent edibles.”

Another incentive for dispensaries to test is the intrinsic marketing value. It behooves dispensaries to be able to label certain strains as high in CBD (which is a non-psychoactive part of the plant with impressive health benefits) or THC, because they can mark up the prices on those now-specialty products.

“Just like aspirin, you wouldn’t get any other over-the-counter drug, if you don’t really know the active content of milligrams or what ingredients are in it,” Dixon said. “In California, since there’s been such stagnation from the state to bring about regulation, it’s just a county by county, city by city thing and California’s still pretty far behind [as far as actual regulation]. I definitely commend states like Colorado and Washington.”

Dixon said SC Labs, and most others, base their testing procedures on pre-established testing requirements in places like the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, and the Dutch government, both of which have been testing cannabis for potency and food safety for years.

“We have these different references of established standards, national and international that are used to test different active compounds in cannabis,” he said. “And then we have other like industries, or other like crops, to establish microbiological contamination limits. We’re using different validated, internationally accepted instruments and methods to do the testing.”

A Look at Colorado’s New Requirements

Colorado’s first testing labs popped up shortly following California’s, and while the mile-high state didn’t invent the cannabis testing lab, today it is home to some of the most advanced cannabis businesses in the nation. For some of those businesses, the state’s new requirements won’t be hard to implement because cutting-edge testing labs are already part of their operations.

Four years ago, before recreational marijuana was legalized and before the state required any testing for cannabis products, an edible cannabis company called Dixie Elixirs arrived on the scene in Denver. Today it supplies THC-infused edibles and beverages as well as non-psychoactive CBD-rich topical oils and creams to pot shops and medical dispensaries. Its business is set up so that it is a testing lab and infused-cannabis products manufacturer in one. Its THC-infused products range from cookies and fudge to mints and a THC-infused pomegranate elixir. Before mixing any cannabis extracts into its products, they are tested in an in-house scientific lab.

Christie Lunsford, marketing director of Dixie Elixirs, says the company has had a goal since its founding to be ahead of the curve. She said the company’s self-imposed standards will likely exceed any state regulations, and she’s glad other businesses will be held to a specific standard, too.

“We make sure if I’m saying these two truffles are 100 milligrams of THC, the consumer knows they really have 100 milligrams of THC, and they have a predictable, safe and fun experience,” she said. “That’s my mantra: predictable, fun and safe.”

Dixie Elixirs’ lab tests each cannabis product three times. Once when they receive the raw plant material, once when they extract the THC-rich CO2 oil (which is their extraction process), and again when they spot-check each batch to make sure their math is accurate and the dose on the label matches the dose in the product.

The challenge of edible production is that it’s much easier to tack a general potency level onto the whole edible than it is to give a dosage per bite, because of the nature of making edibles. If you were going to make edibles in your kitchen, you’d be using extracted butter or oil and just mixing it into a batch of cookies or brownies. The chances of that extraction getting spread perfectly evenly from bite to bite would be slim. Lunsford said Dixie Elixirs has gotten its lab procedures down to a near-exact science so that even its 10 milligram “metamints,” which are breath mints the size of a pinky fingernail, are coming out evenly.

“We recently tested 10 10-milligram metamints, and they each came back as 9.7, 9.6, 9.8, and several came back at exactly 10 milligrams,” she said. “I remember when edibles were produced in someone’s kitchen, and they were well-intentioned but that’s when things were scary because you didn’t know how much you were getting. Because we are an industry in Colorado that welcomes and works with regulatory framework, we’ve been able to give consumers a predictable experience. We have developed a framework together for what’s appropriate.”

This is an expanded version of an earlier AlterNet article by April M. Short, published in March.