A new national report dispels the common prohibitionist argument.

The U.S. federal government stubbornly continues to classify marijuana as a Schedule I substance with no known medical uses. While our government blocks all research on the potential benefits of marijuana, clinical studies in Israel, Spain and elsewhere confirm what patients in the 23 U.S. states with medical marijuana programs already know: it’s a miraculous treatment option for many known diseases, with the potential to mitigate, and sometimes reverse, ailments ranging from cancer, PTSD and epilepsy to arthritis, skin abrasions, and chronic pain.

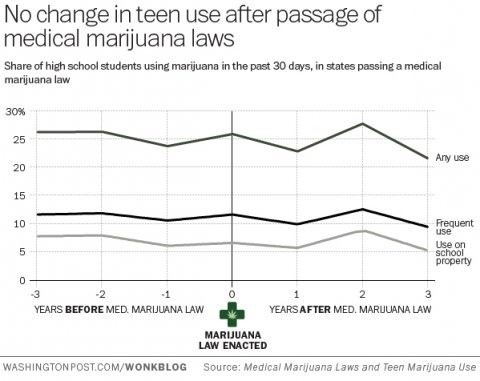

Since so many of the arguments against cannabis medicine are crumbling, marijuana prohibitionists are resorting to fear-mongering about the “safety of the children” to defend their position. They insist that allowing marijuana in any form will give kids the impression it’s okay to toke up, and teen marijuana use will spike.

But that argument is baseless, according to a new report by D. Mark Anderson, Benjamin Hansen, and Daniel I. Rees of the National Bureau of Economic Research. The report, released in July, shows that the presence of medical marijuana does not lead to increased use among teens.

As the report abstract states:

While at least a dozen state legislatures in the United States have recently considered bills to allow the consumption of marijuana for medicinal purposes, the federal government is intensifying its efforts to close medical marijuana dispensaries. Federal officials contend that the legalization of medical marijuana encourages teenagers to use marijuana and have targeted dispensaries operating within 1,000 feet of schools, parks and playgrounds…. Our results are not consistent with the hypothesis that legalization leads to increased use of marijuana by teenagers.

The researchers estimated the relationship between medical marijuana laws and teen marijuana consumption by using data from the national and state Youth Risk Behavior Surveys (which is conducted biennially by the Centers for Disease Control and used by federal agencies to track trends in adolescent behavior). It also used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth in 1997 and the Treatment Episode Data Set. They assessed the 16 states that had legalized medical marijuana between 1993 and 2011 (including Alaska, California, Maine, Oregon and Washington) and tracked self-reported teen pot use in the years leading up to medical marijuan laws, and then following legalization.

The researchers found that the hypothesis that the legalization of medical marijuana causes increased pot use among high school students is unfounded. They found that the impact of medical marijuana laws on teens was “small, consistently negative, and never statistically distinguishable from zero.”

The following chart (pulled from the report by the Washington Post), shows trending teen marijuana use according to state YRBS data. The x-axis tracks the three-year periods before and after medical marijuana laws were passed in each state (including Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Delaware, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico and Vermont). As the Washington Post put it, “the lines are essentially flat.”