The pledge to wage “relentless warfare” on drugs was first made in the 1930s, by a man who has been largely forgotten today.

The following is an excerpt from Johann Hari’s new book, Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs (Bloomsbury, 2015).

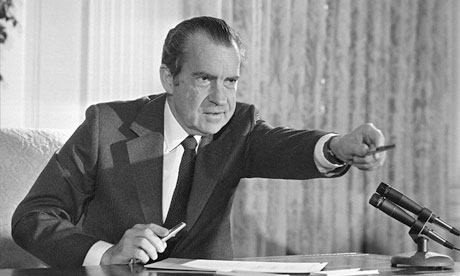

As I waited in the drowsy neon-lit customs line at JFK, I tried to remember precisely when the war on drugs started. In some vague way, I had a sense that it must have been with Richard Nixon in the 1970s, when the phrase was first widely used. Or was it with Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, when “Just Say No” seemed to become the second national anthem?

But when I started to travel around New York City interviewing experts on drug policy, I began to get a sense that this whole story had, in fact, begun long before. The pledge to wage “relentless warfare” on drugs was, I found, first made in the 1930s, by a man who has been largely forgotten today—yet he did more than any other individual to create the drug world we now live in. I learned there are vast forgotten piles of this man’s paperwork at Penn State University—his diary, his letters, all his files—so I headed there on a Greyhound bus, and began to read through everything I could find by and about Harry Anslinger. Only then did I begin to see who he really was—and what he means for us all.

In those files, I learned that at the birth of the war on drugs, there were three people who could be seen as its founding figures: if there was a Mount Rushmore for drug prohibition, it is their faces who would be carved into its mountainside, staring impassively back, slowly eroding. I chased the information about them across many more archives, and to the last remaining people to remember them. Now, three years later, after all I have learned, I find myself picturing these founding figures as they were when the drug war clouds first began to gather—as kids, scattered across the United States, not knowing what was about to hit them, or what they would achieve. That is where, it seems to me, this story begins.

***

In 1904, a twelve-year-old boy was visiting his neighbor’s farmhouse in the cornfields of western Pennsylvania when he heard a scream. It was coming from somewhere above him. This sound—desperate, aching— made him confused. What was going on? Why would a grown woman howl like an animal?

Her husband ran down the stairs and gave the boy a set of hurried instructions: Take my horse and cart into the town as fast as you can. Pick up a package from the pharmacy. Bring it here. Do it now.

The boy lashed at the horses, because he was certain that if he failed, he would return to find a corpse. As soon as he flopped through the door and handed over the bag of drugs, the farmer ran to his wife. Her screaming stopped, and she was calm. But the boy would not be calm about this—not ever again.

“I never forgot those screams,” he wrote years later. From that moment on, he was convinced there was a group of people walking among us who may look and sound normal, but who could at any moment become “emotional, hysterical, degenerate, mentally deficient and vicious” if they were allowed contact with the great unhinging agent: drugs.

When he grew into a man, this boy was going to draw together some of the deepest fears in American culture—of racial minorities, of intoxication, of losing control—and channel them into a global war to prevent those screams. It would cause many screams in turn. They can be heard in almost every city on earth tonight.

This is how Harry Anslinger entered the drug war.

***

On a different afternoon a few years earlier, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, a wealthy Orthodox Jewish trader walked in on a scene that he could not understand. His three-year-old son was standing over his sleeping older brother holding a knife, ready to stab him. “Why, my son, why?” the trader asked. The little boy said that he hated his brother.

The boy was going to hate a lot of people in his life—almost everyone, in fact. He would later declare that “the majority of the human race are dubs and dumbbells and have rotten judgment and no brains.” He would plunge his knife into many people, as soon as he had gained enough wealth and power to get other people to wield the weapon. Normally a man with his personality type would end up in prison, but this little boy didn’t. He was handed an industry where his capacity for violence was not just rewarded, but required: the new market for illegal drugs in North America. When he was finally shot—separated by twenty blocks, countless killings, and many millions of dollars from his sleeping brother on that night—he was a free man.

This is how Arnold Rothstein entered the drug war.

***

On yet another afternoon, in 1920, a six-year-old girl lay on the floor of a brothel in Baltimore listening to jazz records. Her mother was convinced this music was the work of Satan and wouldn’t let her hear a note of it at home, so the child offered to perform small cleaning tasks for the madam of the local whorehouse on one condition: instead of being paid a nickel like the other kids, she would take her pay on this floor, in rapt hours left alone to listen. It gave her a feeling she couldn’t describe—and she was determined, one day, to create this feeling in other people.

Even after she was raped, and after she was pimped, and after she started to inject heroin to take away the pain, this music would still be there waiting for her.

This is how Billie Holiday entered the drug war.

***

When Harry and Arnold and Billie were born, drugs were freely available throughout the world. You could go to any American pharmacy and buy products made from the same ingredients as heroin and cocaine. The most popular cough mixtures in the United States contained opiates, a new soft drink called Coca-Cola was made from the same plant as snortable cocaine, and over in Britain, the classiest department stores sold heroin tins for society women.

But they lived at a time when American culture was looking for an outlet for its swelling tide of anxiety—a real, physical object it could destroy, in the hope that this would destroy its fear of a world that was changing more rapidly than their parents and grandparents could ever have imagined. It settled on these chemicals. In 1914—a century ago— they resolved: Destroy them. Wipe them from the earth. Set yourself free.

As this decision was made, Harry and Arnold and Billie found themselves scattered across that first battlefield, and pressed into combat.

***

When Billie Holiday stood on stage, her hair was pulled back tightly, her face was round and shining in the lights, and her voice was scratched with pain. It was on one of these nights, in 1939, that she started to sing a song that would become iconic:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root.

Before, black women had—with very few exceptions—been allowed on stage only as beaming caricatures, stripped of all real feeling. But now, here, she was Lady Day, a black woman expressing grief and fury at the mass murder of her brothers in the South—their battered bodies hanging from the trees.

“It was extremely brave, when you think about it,” her goddaughter Lorraine Feather told me. At that time, “every song was about love. You simply did not have a piece of music being performed at some hotel that was about the killing of people—about such a sordid and cruel fact. It was not done. Ever.” And to have an African American woman doing such a song? About lynching? But Billie did it because the song “seemed to spell out all the things that had killed” her father, Clarence, in the South.

The audience listened, hushed. Many years later, this moment would be called “the beginning of the civil rights movement.” Lady Day was ordered by the authorities to stop singing this song. She refused.

Her harassment by Harry’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics began the next day. Before long, he would play a crucial role in killing her.

***

From his first day in office, Harry Anslinger had a problem, and everybody knew it. He had just been appointed head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics—a tiny agency, buried in the gray bowels of the Treasury Department in Washington, D.C.—and it seemed to be on the brink of being abolished. This was the old Department of Prohibition, but prohibition had been abolished and his men needed a new role, fast. As he looked over his new staff just a few years before his pursuit of Billie began, he saw a sunken army who had spent fourteen years waging war on alcohol only to see alcohol win, and win big. These men were notoriously corrupt and crooked—but now Harry was supposed to whip them into a force capable of wiping drugs from the United States forever.

And that was only the first obstacle. Many drugs, including marijuana, were still legal, and the Supreme Court had recently ruled that people addicted to harder drugs should be dealt with by doctors, not bang’em-up men like Harry. And then—almost before he had settled into his office chair—Harry’s budget was slashed by $700,000. What was the point of this department, this position, this work? It seemed his new kingdom of drug prohibition could crumble into bureaucratic history at any moment.

Within a few years, the stress of trying to hold this together and creating a role for himself would make all of Harry’s hair fall out and leave him looking, according to his staff, like a wrestler printed in primary colors on a fading poster.

Harry believed that the response to being dealt a weak hand should always be to dramatically raise the stakes. He pledged to eradicate all drugs, everywhere—and within thirty years, he succeeded in turning this crumbling department, with these disheartened men, into the headquarters for a global war that would last for a hundred years and counting. He could do it because he was a bureaucratic genius—and, even more crucially, because there was a deep strain in American culture that was waiting for a man like him, with a sure and certain answer to their questions about chemicals.

Ever since that day in his neighbor’s farmhouse, Harry had known that he wanted to lead the charge to wipe drugs from the earth—but nobody imagined that, from where he started, he could ever do it, never mind so quickly. His dad was a Swiss hairdresser who had fled his home in the mountains to avoid military conscription and eventually washed up in Pennsylvania, where he had nine kids. He couldn’t afford much schooling for them, so when the eighth child, Harry, was fourteen, he was forced to go out to work on the railroad. He was a determined boy, and he insisted on working for money in the afternoons and evenings so he could keep going to school every morning.

But it was in his paid work that Harry got his greatest education; there, laying the train tracks for the state of Pennsylvania, he got his first glimpse of something dark and hidden—and it would become his second lifelong obsession. It was his task to supervise a large number of recent Sicilian immigrants. Sometimes, he wrote, he heard them talking darkly in hushed asides about something called a “Black Hand.”

Harry recorded their thoughts in the style of the pulp fiction thrillers he was obsessed with. You didn’t mention it in front of strangers. You didn’t mention it even in front of your family unless you had to. But it could destroy you with one swipe. What could this Black Hand be? Nobody would tell.

But one morning, Harry found one of his work crew—an Italian man named Giovanni—bleeding in a ditch. He had been shot multiple times. When Giovanni woke up in the hospital, Harry was there, ready to hear what had happened, but the workman was too terrified to speak. Anslinger spent hours assuring him that he could keep him and his family safe.

Finally, Giovanni spoke. He said he was being forced to pay protection money by a man called “Big Mouth Sam,” one of the thugs belonging to a group called the Mafia that had come to the United States from Sicily and remained hidden amidst the Italian immigrants. The Mafia, Giovanni told Harry, were engaged in all sorts of crimes, and people on the railroad were being charged a “terror tax”—you gave the Mafia money or else you ended up in a hospital bed like this, or worse.

Anslinger went to confront Big Mouth Sam—a “squat, black-haired and ox-shouldered” immigrant—and said, “If Giovanni dies, I’m going to see to it that you hang. Do you understand that?” Big Mouth tried to reply, but Harry insisted: “And if he lives and you ever bother him again, or any of my men, or try to shake any of them down any more, I’ll kill you with my own hands.”

After that, Anslinger became obsessed with the Mafia, at a time when most Americans refused to believe it even existed. This is hard for us to understand today, but the official position of every official in U.S. law enforcement until the 1960s—from J. Edgar Hoover on down—was that the Mafia was a preposterous conspiracy theory, no more real than the Loch Ness Monster. They reacted the way we would now if a law enforcement agent preached Trutherism, or Birtherism, or the belief that Freemasons are secretly manipulating world events: with bafflement at the idea that anyone could believe something so silly.

But Harry had glimpsed the Mafia in the flesh, and he was convinced that if he followed the trail from Big Mouth Sam to the thugs above him and the thugs above them, he would be led to a vast global web, and perhaps even to an “invisible worldwide government” secretly controlling events. He soon started keeping every scrap of information he could find on the Mafia, no matter how small or how trivial the source. He snipped small stories from pulp magazines and stored them away: one day, he thought, he would use this information.

As soon as the First World War started, Harry tried to sign up for the military, but he was blind in one eye—his brother had hit him with a rock years before—and was turned down. But since he spoke fluent German, he was offered a position as a diplomatic agent in Europe, and before long he was traveling on a boat to London, through a fog that had left the British Isles invisible and lost. From there, he traveled on to Hamburg and The Hague, where his job was to ferret out information from local diplomats and to deal with local Americans in trouble. Several discharged American sailors were brought to him to be shipped home because they had become addicted to heroin. Harry stared into their skeletal faces and found that the hatred he felt as a small boy was only swelling. This, he promised himself, would be stopped.

At the very end of the war, as it was becoming clear to everyone that the Germans had lost, Harry was sent on his most important mission so far: to take a secret message to the defeated German dictator. The way he later told the story, Harry was dispatched to the small Dutch town of Amerongen, where the Kaiser was holed up in a castle and planning to abdicate. Anslinger’s job was to pose as a German official and convey a message from President Woodrow Wilson: Don’t do it. The United States wanted the Kaiser to retain the imperial throne, to prevent the rise of the “revolution, strikes and chaos” it feared would follow from his sudden departure.

The Dutch guards at the gates of the castle ordered Harry to show his credentials. “Show me your credentials,” he snapped back in his fiercest German. Frightened, assuming he was one of the Kaiser’s men, they let him through.

Anslinger managed to get the message through—but it was too late. The decision had been made. The Kaiser quit. For the rest of his life, Anslinger believed that if he had gotten the president’s plea through only a little earlier, “a decent peace might have been written, forestalling any chance for a future Hitler gaining power, or a Second World War erupting.” It was the first time Harry felt that the future of civilization hung on his actions, but it would not be the last.

He traveled across a Europe in rubble. “The sight of a large city in ruins, without a house seen standing, creates a feeling that is hard to describe,” he wrote in his diary. Bombed bridges lay as wreckage. Factories were either destroyed entirely, or had all their machinery ripped from them, and often dumped along the roadsides, twisted and useless, like metal ghosts of the time before. There were enormous shell-holes, and acres of barbed wire. Whatever you imagined before, he wrote, “magnify the imagination by twenty times.”

But what shook Harry most was the effect of the war not on the buildings but on the people. They seemed to have lost all sense of order. Starving, they had begun to riot; the cavalry had been sent to charge against them, and entire streets were on fire. Harry was standing in a hotel lobby in Berlin when Socialist revolutionaries suddenly fired their machine guns into the lobby, and blood from a bystander splattered onto his hands. Civilization, he was beginning to conclude, was as fragile as the personality of that farmer’s wife back in Altoona. It could break. After this, and for the rest of his life, Harry retained a deep sense that American society could collapse into wreckage just as quickly as Europe’s had.

In 1926, he was redeployed from the gray wreckage of Europe to the blue-watered island of the Bahamas, but Harry was not a man looking for a reason to relax. This was the height of alcohol prohibition: Americans wanted to drink, and smugglers wanted to sell to them, so whisky was washing through these islands like water. Harry was outraged. The bootleggers were West Indian and Central American, and he believed they were filled with “loathsome and contagious diseases” that would spread to anyone foolish enough to drink the booze they handled.

“Just give me a high-powered rifle. I’ll stop the bastards,” one of Harry’s colleagues said, and in this spirit, Harry announced to his bosses that there was a way to make prohibition work: Use maximum force. Send the navy to hunt down smugglers along the coasts of America. Ban the sale of alcohol for medical purposes. Massively increase prison sentences for alcohol dealers until they were all locked up. Wage war on booze until it was only a memory.

In just a few years, Harry made the leap from being a competent if frustrated prohibition agent in the Bahamas to running a Washington, D.C., department. How did he do it? It’s hard to tell, but it must have helped that he married a young woman named Martha Denniston who was from one of the richest families in America, the Mellons. The treasury secretary, Andrew Mellon, was now a close relative—and the prohibition department was part of the Treasury itself.

***

From the moment he took charge of the bureau, Harry was aware of the weakness of his new position. A war on narcotics alone—cocaine and heroin, outlawed in 1914—wasn’t enough. They were used only by a tiny minority, and you couldn’t keep an entire department alive on such small crumbs. He needed more.

With this in mind, he had begun noticing stories in the newspapers that intrigued him. They had headlines like the one in the July 6, 1927, edition of the New York Times: mexican family go insane. It explained: “A widow and her four children have been driven insane by eating the Marihuana plant, according to doctors who say there is no hope of saving the children’s lives and that the mother will be insane for the rest of her life.” The mother had no money to buy food, so she decided to eat some marijuana plants that had been growing in their garden. Soon after, “neighbors, hearing outbursts of crazed laughter, rushed to the house to find the entire family insane.”

Harry had long dismissed cannabis as a nuisance that would only distract him from the drugs he really wanted to fight. He insisted it was not addictive, and stated “there is probably no more absurd fallacy” than the claim that it caused violent crime.

But almost overnight, he began to argue the opposite position. Why? He believed the two most-feared groups in the United States—Mexican immigrants and African Americans—were taking the drug much more than white people, and he presented the House Committee on Appropriations with a nightmarish vision of where this could lead. He had been told, he said, of “colored students at the University of Minn[esota] partying with female students (white) and getting their sympathy with stories of racial persecution. Result: pregnancy.” This was the first hint of much more to come.

He wrote to thirty scientific experts asking a series of questions about marijuana. Twenty-nine of them wrote back saying it would be wrong to ban it, and that it was being widely misrepresented in the press. Anslinger decided to ignore them and quoted instead the one expert who believed it was a great evil that had to be eradicated.

On this basis, Harry warned the public about what happens when you smoke this weed. First, you will fall into “a delirious rage.” Then you will be gripped by “dreams . . . of an erotic character.” Then you will “lose the power of connected thought.” Finally, you will reach the inevitable end point: “Insanity.” You could easily get stoned and go out and kill a person, and it would all be over before you even realized you had left your room, he said, because marijuana “turns man into a wild beast.” Indeed, “if the hideous monster Frankenstein came face to face with the monster Marijuana, he would drop dead of fright.”

A doctor called Michael V. Ball got in touch with Harry to counter this view, saying he had used hemp extract as a medical student and it only made him sleepy. He suspected that the claims circulating about the drug couldn’t possibly be true. Maybe, he said, cannabis does drive people crazy in a tiny number of cases, but his hunch was that anybody reacting that way probably had an underlying mental health problem already. He implored Anslinger to fund proper lab studies so they could find out the truth.

Anslinger wrote back firmly. “The marihuana evil can no longer be temporized with,” he explained, and he would fund no independent science, then or ever.

For years, doctors kept approaching him with evidence that he was wrong, and he began to snap, telling them they were “treading on dangerous ground” and should watch their mouths. Instead, he wrote to police officers across the country commanding them to find him cases where marijuana had caused people to kill—and the stories started to roll in.

The defining case for Harry, and for America, was of a young man named Victor Lacata. He was a twenty-one-year-old Florida boy known in his neighborhood as “a sane, rather quiet young man” until—the story went—the day he smoked cannabis. He then entered a “marihuana dream” in which he believed he was being attacked by men who would cut off his arms, so he struck back, seizing an axe and hacking his mother, father, two brothers, and sister to pieces.

The press, at Harry’s prompting, made Lacata’s story famous. If your son smoked marijuana, people came to believe, he, too, could hack you to pieces. Anslinger was not the originator of these arguments—they had actually been widespread in Mexico in the late nineteenth century, where it was pervasively believed that marijuana made you “loco.” Nor was he the only one pushing them in the United States—the press loved these stories, especially the mass media owned by William Randolph Hearst. But for the first time, Anslinger gave them the backing of a government department that would broadcast them to the nation at full volume, with an official government stamp saying they were true. From the clouds of cannabis smoke, he warned, there were Victor Lacatas rising all around us.

The warnings worked. People began to clamor for the Bureau of Narcotics to be given more money to save them from this terrifying threat. Harry’s problem—the fragility of his new empire—was starting to ease.

Many years later, the law professor John Kaplan went back to look into the medical files for Victor Lacata. The psychiatrists who examined him said he had long suffered from “acute and chronic” insanity. His family was full of people who suffered from similarly extreme mental health problems—three had been committed to insane asylums—and the local police had tried for a year before the killings to get Lacata committed to a mental hospital, but his parents insisted they wanted to look after him at home. The examining psychiatrists thought his cannabis use was so irrelevant that it wasn’t even mentioned in his files.

But Anslinger had his story now. He announced on a famous radio address: “Parents beware! Your children . . . are being introduced to a new danger in the form of a drugged cigarette, marijuana. Young [people] are slaves to this narcotic, continuing addiction until they deteriorate mentally, become insane, [and] turn to violent crime and murder.”

Harry was sticking to this story whatever he was told—in part because, while he was asserting against a wall of skepticism that marijuana drove you mad, he was discovering something incredible. Everybody had mocked him when he said the Mafia existed. Where’s your evidence? they asked, witheringly. But now, through his agents, Anslinger was uncovering proof that the Mafia not only existed, but was bigger than anyone had imagined. He was building up a scrapbook containing the names of details of eight hundred mafiosi operating in the continental United States. His raids were proving him right, but the authorities still refused to believe him, preferring to look away, awkwardly. Some were corrupt; some simply didn’t want to disturb their 100 percent clean-up records by taking on such a difficult and messy crusade; and some were frightened. When the police chief of New Orleans, David Hennessy, started to dig too deeply into the Mafia, he was murdered.

Anslinger began to believe all his hunches would turn out like this. He only had to defy the “experts” and keep pursuing his instinct until, finally, he would be shown to be more right than anyone could have predicted.

He ramped up his campaign. The most frightening effect of marijuana, Harry warned, was on blacks. It made them forget the appropriate racial barriers—and unleashed their lust for white women. Of course, everyone spoke about race differently in the 1930s, but the intensity of Harry’s views shocked people even then, and when it was revealed he’d referred to a suspect in an official memo as a “nigger,” Senator Joseph P. Guffey of Anslinger’s home state of Pennsylvania demanded his resignation. Later, when one of his very few black agents, William B. Davis, complained about being called a “nigger” by Harry’s men, Anslinger sacked him.

Harry soon started treating all his critics this way. When the American Medical Association issued a report debunking some of his more overheated claims, he announced that any of his agents caught with a copy would be immediately fired. Then, when he found out a professor named Alfred Lindesmith was arguing that addicts need to be treated with compassion and care, Harry instructed his men to falsely warn Lindesmith’s university that he was associated with a “criminal organization,” had him wiretapped, and sent a team to tell him to shut up. Harry couldn’t control the flow of drugs, but he was discovering he could control the flow of ideas—and it was not only scientists Harry believed he had to silence.

It was clear from Harry’s writings that he was obsessed with Billie Holiday, and I sensed there might be a deeper story there. So I tracked down everyone who was still alive who had known Billie, to ask them about this, and one of them—her godson, Bevan Dufty—explained that his mother had been Billie’s best friend, and she believed Billie was in effect killed by the authorities. He had the remaining scraps of her writings on this in his attic, where they had been unseen for years. Would you like, he asked, to see them? When I put them together with Harry’s files, what her friends had told me, and the work of her biographers, I began to see this story more clearly.

***

Jazz was the opposite of everything Harry Anslinger believed in. It is improvised, and relaxed, and free-form. It follows its own rhythm. Worst of all, it is a mongrel music made up of European, Caribbean, and African echoes, all mating on American shores. To Anslinger, this was musical anarchy, and evidence of a recurrence of the primitive impulses that lurk in black people, waiting to emerge. “It sounded,” his internal memos said, “like the jungles in the dead of night.” Another memo warned that “unbelievably ancient indecent rites of the East Indies are resurrected” in this black man’s music. The lives of the jazzmen, he said, “reek of filth.”

His agents reported back to him that “many among the jazzmen think they are playing magnificently when under the influence of marihuana but they are actually becoming hopelessly confused and playing horribly.”

The Bureau believed that marijuana slowed down your perception of time dramatically, and this was why jazz music sounded so freakish—the musicians were literally living at a different, inhuman rhythm. “Music hath charms,” their memos say, “but not this music.” Indeed, Harry took jazz as yet more proof that marijuana drives people insane. For example, the song “That Funny Reefer Man” contains the line “Any time he gets a notion, he can walk across the ocean.” Harry’s agents warned: “He does think that.”

Anslinger looked out over a scene filled with men like Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, and Thelonious Monk, and—as the journalist Larry Sloman recorded—he longed to see them all behind bars. He wrote to all the agents he had sent to follow them, and instructed: “Please prepare all cases in your jurisdiction involving musicians in violation of the marijuana laws. We will have a great national round-up arrest of all such persons on a single day. I will let you know what day.” His advice on drug raids to his men was always “Shoot first.”

He reassured congressmen that his crackdown would affect not “the good musicians, but the jazz type.” But when Harry came for them, the jazz world would have one weapon that saved them: its absolute solidarity. Anslinger’s men could find almost no one among them who was willing to snitch, and whenever one of them was busted, they all chipped in to bail him out.

In the end, the Treasury Department told Anslinger he was wasting his time taking on a community that couldn’t be fractured, so he scaled down his focus until it settled like a laser on a single target—perhaps the greatest female jazz vocalist there ever was.