Bloodletting was treatment for infection in the past.

The development of antibiotics and other antimicrobial therapies is arguably the greatest achievement of modern medicine. However, overuse and misuse of antimicrobial therapy predictably leads to resistance in microorganisms. Alternative therapies have been used to treat infections since antiquity, but none are as reliably safe and effective as modern antimicrobial therapy. So how were infections treated before antimicrobials were developed in the early 20th century?

Blood, leeches and knives

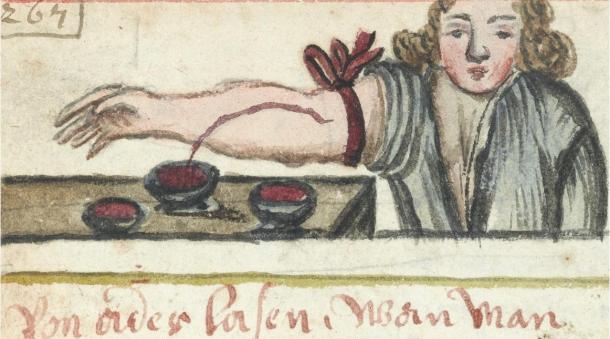

Bloodletting was used as a medical therapy for over 3,000 years. It originated in Egypt in 1000 B.C. and was used until the middle of the 20th century.

Medical texts from antiquity all the way up until 1940s recommend bloodletting for a wide variety of conditions, but particularly for infections. As late as 1942, William Osler’s 14th edition of Principles and Practice of Medicine, historically the preeminent textbook of internal medicine, included bloodletting as a treatment for pneumonia.

Bloodletting is based on an ancient medical theory that the four bodily fluids, or “humors” (blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile), must remain in balance to preserve health. Infections were thought to be caused by an excess of blood, so blood was removed from the afflicted patient. One method was to make an incision in a vein or artery, but it was not the only one. Cupping was another common method, in which heated glass cups were placed on the skin, creating a vacuum, breaking small blood vessels and resulting in large areas of bleeding under the skin. Most infamously, leeches were also used as a variant of bloodletting.

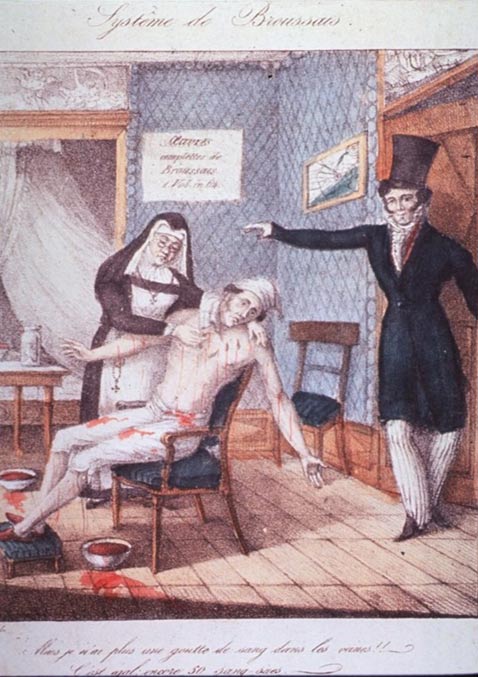

A man sitting in chair, arms outstretched, streams of blood pouring out as a nun places leeches on his body. Images from the History of Medicine (NLM)

Interestingly, though bloodletting was recommended by physicians, the practice was actually performed by barbers, or “barber-surgeons.” The red and white striped pole of the barbershop originated as “advertising” their bloodletting services, the red symbolizing blood and the white symbolizing bandages.

There may actually have been some benefit to the practice – at least for certain kinds of bacteria in the early stages of infection. Many bacteria require iron to replicate, and iron is carried on heme, a component of the red blood cell. In theory, fewer red blood cells resulted in less available iron to sustain the bacterial infection.

Some mercury for your syphilis?

Naturally occurring chemical elements and chemical compounds have historically have been used as therapies for a variety of infections, particularly for wound infections and syphilis.

A woodcut from 1689 showing various methods of syphilis treatment including mercury fumigation. Images from the History of Medicine (NLM)

Topical iodine, bromine and mercury-containing compounds were used to treat infected wounds and gangrene during the American Civil War. Bromine was used most frequently , but was very painful when applied topically or injected into a wound, and could cause tissue damage itself. These treatments inhibited bacterial cell replication, but they could also harm normal human cells.

Mercury compounds were used to treat syphilis from about 1363 to 1910. The compounds could be applied to skin, taken orally or injected. But the side effects could include extensive damage to skin and mucous membranes, kidney and brain damage, and even death. Arsphenamine, an arsenic derivative, was also used in the first half of the 20th century. Though it was effective, side effects included optic neuritis, seizures, fever, kidney injury and rash.

Thankfully, in 1943, penicillin supplanted these treatments and remains the first-line therapy for all stages of syphilis.

Looking in the garden

Over the centuries, a variety of herbal remedies evolved for the treatment of infections, but very few have been evaluated by controlled clinical trials.

One of the more famous herbally derived therapies is quinine, which was used to treat malaria. It was originally isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree, which is native to South America. Today we use a synthetic form of quinine to treat the disease. Before that, cinchona bark was dried, ground into powder, and mixed with water for people to drink. The use of cinchona bark to treat fevers was described by Jesuit missionaries in the 1600s, though it was likely used in native populations much earlier.

An engraving of a Quinine plant, 1880. Wellcome Library, London, CC BY

Artemisinin, which was synthesized from the Artemisia annua (sweet wormwood) plant is another effective malaria treatment.

A Chinese scientist, Dr. Tu Youyou , and her team analyzed ancient Chinese medical texts and folk remedies, identifying extracts from Artemisia annua as effectively inhibiting the replication of the malaria parasite in animals.

Tu Youyou was coawarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of artemisinin.