“What permaculturists are doing is the most important activity that any group is doing on the planet.” – David Suzuki

A Brief History of Agriculture

Before we look at what the future might look like we need to understand how we got to where we are before we can move in the appropriate direction for a new and more sustainable future.

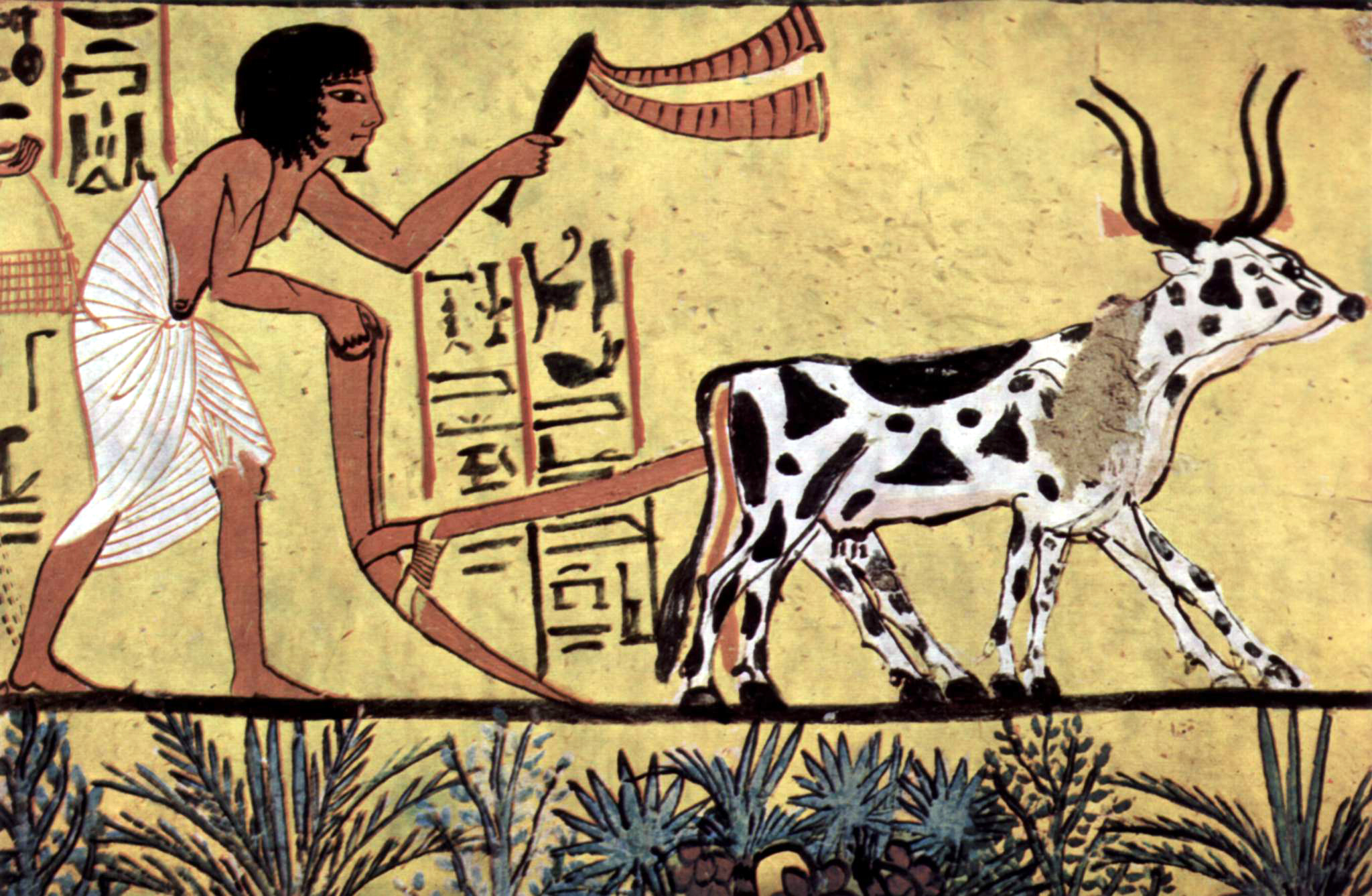

Scholars, historians and archaeologists suggest that various forms of farming have existed for over 10,000 years. It was around 9500 BC that the development of crops such as wheat, barley, peas and lentils occurred in the Eastern Mediterranean region (Syria, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, and Palestinian Territories). In 5500 BC in Southern Mesopotamia, the Sumerians developed possibly the first large scale intensive farming system that included mono cropping -the use of organised labour and widespread irrigation. In 4000 BC, the Mesopotamians were at it again, developing wooden ploughs, possibly the first in history. It took the Assyrian’s another five hundred years to develop irrigation techniques. At the same time, 3500 BC, evidence of the first agriculture in the Americas and Central Amazonia occurred. In 500 BC, the Chinese invented an iron plough that saw the development of row cultivation in cropping.

Agriculture moved into a new era with the development of cash cropping in 1000 AD. This was effectively a move away from subsistence farming. In subsistence agriculture, crops are grown mainly for the producers own benefit and consumption. Cash cropping is where crops are grown specifically for sale and profit. In Illinois 1837, John Deere invented the steel plough and by 1855 Deere had sold over 10,000 ploughs across America. 1895 brought with it the development of refrigeration in the United States and United Kingdom which helped in storing excess food supplies for domestic and commercial uses. By 1944 the ‘Green Revolution’ had spread its wings and was transferring technological research and development initiatives across India and other parts of the globe. This revolution helped increase production in countries like India with the development of higher yielding crop varieties. The ‘green revolution’ introduced intensive irrigation methods and manmade fertilizers and pesticides.

A Summary of Current and previous agricultural production

Looking back over this brief history of agriculture, two key things have occurred in farming. Firstly, there has been a move away from subsistence farming toward cash cropping with an emphasis on increasing yields and output of crop varieties. Secondly, developments in farming techniques and technological improvements over the last century have only been made possible by oil powered machinery and oil based agricultural inputs. These increases in technology and automation have allowed societies to sustain themselves more adequately, allowing populations to increase across all continents. Another trend that is highlighted when looking back at our farming and agriculture history is the predominance of land clearance and intensive farming. There have been some exceptions, many of which are traditional native cultures who saw no need for improved efficiencies as the natural systems and cycles provided enough for a sustained existence. Many of our modern agricultural practices have had a focus on intensive farming that uses heavy machinery, artificial fertilizers and pesticides which eventually depletes soils and the natural environment. The history books are littered with cultures and societies that have collapsed from the exploitation of natural resources. It makes sense that we investigate alternatives to agricultural production going forward. It is estimated that for every calorie of food we eat in the modern industrialised food system it takes 10 calories of fossil fuels to produce that one calorie of food, therefore the price of food and cheap energy are highly correlated. In the early 1900′s 50% of the American workforce was employed in the agricultural sector. Today the number is approximately 2% of the workforce that is engaged in growing food.

Permaculture the Way Forward

The term ‘permaculture’ originated from Australian born author, scientist, teacher and naturalist Bill Mollison and co-developer David Holmgren in the 1970′s. Mollison is known as the ‘father’ of permaculture. He summarises permaculture: “Permaculture (permanent agriculture) as the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have the diversity, stability and resilience of natural ecosystems.” Permaculture has spread across the globe and there are now millions of people practicing and teaching permaculture principles and design. In his book ‘Permaculture: A Designers Manual’ Mollison states “Permaculture in essence is how nature ultimately designed things in the first place. The idea behind permaculture is to replicate or mimic the natural systems and environments, while using some of the modern techniques of horticulture, architecture and agriculture to enhance and yield edible food supplies.” David Holgren in his book Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability elaborates: “Consciously designed landscapes which mimic the patterns and relationships found in nature, while yielding an abundance of food, fibre and energy for provision of local needs,” and, “I see permaculture as the use of systems thinking and design principles that provide the organising framework for implementing the above vision.”

“The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and to take care of it.” – Genesis 2:15

For the most part, we have been following a path of intensive and highly automated agriculture that places pressure on natural systems. Permaculture is more closely linked with how traditional natives farmed and worked with the land. Soil quality is one of the key ingredients for successful farming and agriculture. From the Cuban experience we know that it took the Cubans between 3 to 5 years to get the soil back into a healthy condition after many years of degradation. The use of pesticides, herbicides and artificial fertilisers destroyed the composition of these soils. The methodology that underlies the permaculture movement is that of community and bringing people together to work for the common good. It is a shift away from a non-material profiteering way of life, towards one that encompasses personal responsibility for our actions, taking care of the environment and ensuring that resources are managed sustainability.

Permaculture brings us back to a time when communities, friends and neighbours shared resources. Permaculture is a long way from cheap mass produced food that generate externalities from production. It is about observing nature’s laws and working with nature as opposed to against it. Permaculture is about harnessing what nature has to offer without being greedy and taking more than we need. The collection and storage of water through tanks and the preserving of foods is an example of this philosophy. Realising that what we do today will impact future generations is crucial in paving the way for a sustainable agricultural future. Short sighted profitability must make way for long term sustainability of our land and environment. (1)

Permaculture Design Principles

By taking the time to engage with nature we can design solutions that suit our particular situation. This icon for this design principle represents a person ‘becoming’ a tree. In observing nature it is important to take different perspectives to help understand what is going on with the various elements in the system. The proverb “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” reminds us that we place our own values on what we observe, yet in nature, there is no right or wrong, only different.

By developing systems that collect resources when they are abundant, we can use them in times of need.

This icon for this design principle represents energy being stored in a container for use later on, while the proverb “make hay while the sun shines” reminds us that we have a limited time to catch and store energy.

Ensure that you are getting truly useful rewards as part of the work that you are doing. The icon of this design principle, a vegetable with a bite out of it, shows us that there is an element of competition in obtaining a yield, whilst the proverb “You can’t work on an empty stomach” reminds us that we must get immediate rewards to sustain us.

We need to discourage inappropriate activity to ensure that systems can continue to function well. The icon of the whole earth is the largest scale example we have of a self regulating ‘organism’ which is subject to feedback controls. The proverb “the sins of the fathers are visited unto the children of the seventh generation” reminds us that negative feedback is often slow to emerge.

Make the best use of nature’s abundance to reduce our consumptive behaviour and dependence on non-renewable resources. The horse icon represents both a renewable service and renewable resource. It can be used to pull a cart, plough or log and it can even be eaten – a non consuming use is preferred over a consuming one. The proverb “let nature take it’s course” reminds us that control over nature through excessive resource use and high technology is not only expensive, but can have a negative effect on our environment.

By valuing and making use of all the resources that are available to us, nothing goes to waste. The icon of the worm represents one of the most effective recyclers of organic materials, consuming plant and animal ‘waste’ into valuable plant food. The proverb “a stitch in time saves nine” reminds us that timely maintenance prevents waste, while “waste not, want not” reminds us that it’s easy to be wasteful in times of abundance, but this waste can be a cause of hardship later.

By stepping back, we can observe patterns in nature and society. These can form the backbone of our designs, with the details filled in as we go. Every spider’s web is unique to its situation, yet the general pattern of radial spokes and spiral rings is universal. The proverb “can’t see the forest for the trees” reminds us that the closer we get to something, the more we are distracted from the big picture.

By putting the right things in the right place, relationships develop between them and they support each other. This icon represents a group of people from a bird’s-eye view, holding hands in a circle together. The space in the centre could represent “the whole being greater than the sum of the parts”. The proverb “many hands make light work” suggests that when we work together the job becomes easier.

Small and slow systems are easier to maintain than big ones, making better use of local resources and produce more sustainable outcomes. The snail is both small and slow, it carries its home on its back and can withdraw to defend itself when threatened. The proverb “the bigger they are, the harder they fall” reminds us of the disadvantages of excessive size and growth while “slow and steady wins the race” encourages patience while reflecting on a common truth in nature and society.

Diversity reduces vulnerability to a variety of threats and takes advantage of the unique nature of the environment in which it resides. The remarkable adaptation of the spinebill and hummingbird to hover and sip nectar from long, narrow flowers with their spine-like beak symbolises the specialisation of form and function in nature. The proverb “don’t put all your eggs in one basket” reminds us that diversity offers insurance against the variations of our environment.

The interface between things is where the most interesting events take place. These are often the most valuable, diverse and productive elements in the system. The icon of the sun coming over the horizon with a river in the foreground shows us a world composed of edges. The proverb “don’t think you are on the right track just because its a well-beaten path” reminds us that the most popular is not necessarily the best approach.

We can have a positive impact on inevitable change by carefully observing, and then intervening at the right time. The butterfly is a positive symbol of transformative change in nature, from its previous life as a caterpillar. The proverb “vision is not seeing things as they are but as they will be” reminds us that understanding change is much more than a linear projection. (1)

Permaculture design systems can be used anywhere from rural communities to high density urban environments. The beauty of permaculture is that is about being creative through observing the landscape and adapting and designing around any constraints that may exist. It is about creating a more integrated system that takes into account the natural synergies and connections between components that produce abundance.

Check out this video where a family grows 6,000lbs of produce a year in an urban setting.

Article by Andrew Martin editor of onenesspublishing and author of One ~ A Survival Guide for the Future…

Sources

(1) http://onenesspublishing.com/sample-page/

(2) http://permacultureprinciples.com/principles/