Methane is an extremely baleful greenhouse gas, with more than 20 times the pound-for-pound impact on global warming as CO2. So imagine the alarm scientists felt when they noticed a big ol’ cloud of it, pouring out of the Southwest like noxious vapors from a volcano.

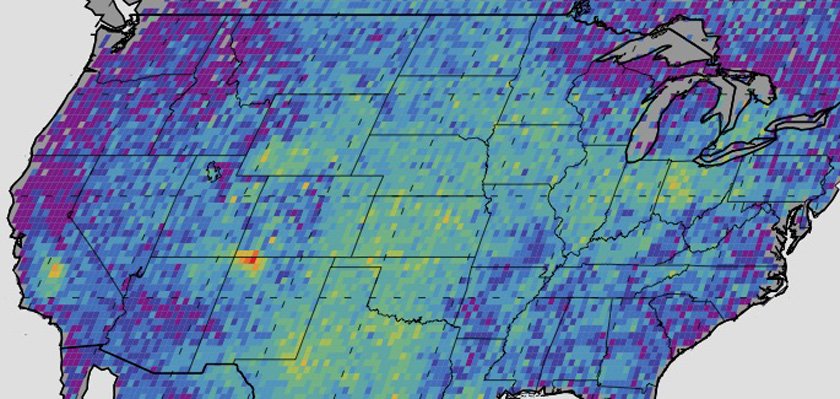

The plume measured half the size of Connecticut and represented the annual release of about 0.59 million metric tons of methane. You can see it floating above the Four Corners region in the above image, which shows how much emissions varied from average background concentrations from 2003 to 2009. While areas with less methane are shown in darker colors, the plume’s intense reds and oranges indicate the discharge of more than three times the amount of gas than what had been recorded on the ground.

Scientists initially couldn’t believe so much methane was rushing out of the dirt. “We didn’t focus on it because we weren’t sure if it was a true signal or an instrument error,” says NASA’s Christian Frankenberg, who first picked up on the gaseous aberration in European satellite data. But experts from the Department of Energy and the University of Michigan verified the widespread leaking, and the guessing game began on where it was coming from.

It couldn’t be fracking, because fracking wasn’t widespread in the region during the cloud’s early years, says Michigan’s Eric Kort, who just published a paper titled “The Largest U.S. Methane Anomaly Viewed from Space.” Instead, he believes the gas is seeping from the San Juan Basin in northwest New Mexico, which NASA calls the “most active coalbed methane production area in the country.” Here is a zoom of the Basin riddled with what looks like industrial outposts:

The huge leaks might’ve gone unnoticed if it hadn’t been for these space-based measurements. (Similar techniques are being used to monitor emissions in Los Angeles.) Here’s Kort again:

The huge leaks might’ve gone unnoticed if it hadn’t been for these space-based measurements. (Similar techniques are being used to monitor emissions in Los Angeles.) Here’s Kort again:

Natural gas is 95-98 percent methane. Methane is colorless and odorless, making leaks hard to detect without scientific instruments.

“The results are indicative that emissions from established fossil fuel harvesting techniques are greater than inventoried,” Kort said. “There’s been so much attention on high-volume hydraulic fracturing, but we need to consider the industry as a whole.”