The Condon Report: Introduction

The “Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects” (Condon & Gillmor 1969; often referred to as the “Condon Report”) presents the findings of the Colorado Project regarding a scientific study of unidentified flying objects. It remains the most influential public document concerning the current scientific status of the UFO issue.

Following is a short chronology of events that led to the Air Force contract with the University of Colorado to initiate the study. This extract is from: “An Analysis of the Condon Report on the Colorado UFO Project,” by P.A. Sturrock, Center for Space Science and Astrophysics, Stanford University. Dr. Sturrock’s analysis is highly recommended as a comprehensive introduction to the text. Additionally, we have included many relevant links that offer further context for the reader.

The history of the UFO phenomenon in the United States is long and complex. Historian David M. Jacobs has provided a comprehensive account of this history in his book “The UFO Controversy in America,” (1975). The book presents a detailed account of the origin of the Colorado UFO Project, of which the following is a brief encapsulation.

The United States Air Force carried out three consecutive studies of the UFO phenomenon over a 22-year period:

2) Project Grudge (1948 to 1952),

3) Project Blue Book (1952 to 1970).

3) Project Blue Book (1952 to 1970).

Although these studies and subsequent reports were initially classified, it appears that all reports (except “Blue Book Special Report No. 13,” if it ever existed) have now been declassified and are publicly available. An exception to this general rule is the “Estimate of the Situation” drafted by Project Sign and referred to by Ruppelt (1956) and Hynek (1972). Blue Book Special Report No. 13 may have been an initial draft of the Battelle study. (Special Report 14)

Two additional scientific studies that occurred within this timeframe deserve mention.

1) For a period of four days in 1953, the Central Intelligence Agency convened a panel of scientific consultants to consider whether UFOs constitute a threat to national defense. This panel included H. P. Robertson (chairman), Luis Alvarez, Lloyd Berkner, Samuel A. Goudsmit and Thornton Page; with Frederick C. Durant and J. Allen Hynek serving as associate members. The panel concluded that there was “no evidence that the phenomena indicate a need for the revision of current scientific concepts,” and that “the evidence . . . shows no indication that these phenomena constitute a direct physical threat to national security” (Jacobs, 1975).

2) The Battelle Memorial Institute, under contract to the Air Force from 1951 to 1954, conducted the second study. It was primarily a statistical analysis of the conditions and characteristics of UFO reports, though it also provided scientific services and included transcripts of several notable sightings. The subsequent report was initially classified, though later released as “Blue Book Special Report No. 14” in 1955. It contains a wealth of information and arrives at the notable conclusion that the more complete the data and the better the report; the more likely it was that the report would remain unidentified (Jacobs, 1975).

On February 3, 1966, the Air Force convened an “Ad Hoc Committee to Review Project Blue Book.” Its members included Brian O’Brien (chairman), Launor Carter, Jesse Orlansky, Richard Porter, Carl Sagan, and Willis A. Ware. The committee recommended that the Air Force negotiate contracts “with a few selected universities to provide selected teams to investigate promptly and in depth certain selected sightings of UFOs.” This led eventually to the Air Force contract with the University of Colorado in October 1966. The project director was Professor Edward U. Condon, a very distinguished physicist and a man of strong and independent character. Work on this contract was carried out over a two-year period with a substantial scientific staff, resulting in the publication of the “Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects” in January 1969.

Consequently, on December 17, 1969, Air Force Secretary Robert C. Seamans, Jr., announced the closure of Project Blue Book. Project Blue Book officially closed on Jan 30, 1970.

In the features Project Sign, and Project Grudge, we saw that, after General Hoyt Vandenburg rejected the conclusions of Project Sign’s 1948 “Estimate of the Situation” as being unfounded, the attitude of the Air Force toward UFOs changed. The name change of its official agent for UFO investigation changed on 16 December 1948 from Project Sign to Project Grudge reflected this change in attitude, as did the final report of Project Sign. On 27 December 1949, a year after its creation, Project Grudge was officially closed and its final report was issued shortly thereafter. It was claimed that the 23 percent of UFO reports that could not be explained by ordinary phenomena could be explained by psychological phenomena.

Project Grudge, however, while “officially” closed, was still functioning at a reduced level. This reduced level consisted of a solitary investigator, Lt. Jerry Cummings. The Project might have faded away altogether except for a series of sightings at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, which resulted in the military itself criticizing the Air Force for its poor investigation of something that seemed to be a threat to national security.

As a result, when Lt. Cummings left the Air Force in 1951, Captain Edward Ruppelt, an Air Force intelligence officer, was appointed to take over the project, which was renamed Project Bluebook. Ruppelt took the task seriously and completely reorganized the project. He established means for speeding the receipt of reports, established liaisons with other agencies, systematized reporting procedures, and obtained the services of a scientific consultant in the person of astronomer Dr. J. Allen Hynek. A standard reporting form was developed by Ohio State University, and the Battelle Memorial Institute was commissioned to do a statistical study known as Project Stork. By April, 1952, after an increase in sighting reports, clearance was given for all intelligence officers at all U.S. Air Force bases to send reports directly to Bluebook by teletype. It seemed that at last the Air Force was truly serious about UFOs. It was just in time for the “flap” of 1952.

The “Flap of 1952” was a huge increase in sightings peaking in July with massive sightings both visual and on radar over Washington, D.C. These sightings were so numerous that they became known as the Washington Nationals. Even the CIA became concerned, so much so that they ordered the Office of Scientific Intelligence to review the data collected by Bluebook and the Air Technical Intelligence Center at Wright-Patterson AFB and to make recommendations based on their findings.

The OSI review of the existing data resulted in a recommendation, predictably, that the phenomena required more study. The main concern of the CIA was not that UFOs were a direct threat to the U.S., but that they were an indirect one. During this period, they heyday of the Cold war, the fear was that the many UFO sighting reports might obscure a very real threat from the Soviet Union. One example was that, during a wave of UFO sightings, a Soviet attack or an overflight by a Russian intelligence-gathering aircraft might not be recognized as such until it was too late.

So, the CIA asked a Cal-Tech physicist, Dr. H.P. Robertson, to assemble a panel of respected scientists to study the UFO phenomenon. These included Dr. Samuel A Goudsmit, a nuclear physicist with the Brookhaven National Laboratories, geophysicist Dr. Lloyd V. Berkner, radar & electronics expert Dr. Luis Alvarez of the University of California, and Johns Hopkins University astronomer Dr. Thornton L. Page. Astronomer and Project Bluebook consultant Dr. J. Allen Hynek and Frederick C. Durant, president of the International Astronautical Foundation, were associate members of the panel.

This distinguished panel, which would become known as the Robertson Panel, spent four days, 14 January, 1953 through 17 January, 1953, reviewing the existing evidence. At the end of this time, they issued a report, known as the “Durant Report”, which merely restated that UFOs were not a direct threat to U.S. security , but which reiterated the fears of the CIA that the Soviets might somehow use the phenomenon to mask an invasions of the United States:

We cite as examples the clogging of channels of communication by irrelevant reports, the danger of being led by continued false alarms to ignore real indications of hostile action, and the cultivation of a morbid national psychology in which skillful hostile propaganda could induce hysterical behavior and harmful distrust of duly constituted authority.

Further, the Panel recommended a policy of debunking UFO sightings in order to quell the growing public preoccupation with the phenomenon:

…the national security agencies take immediate steps to strip the Unidentified Flying Objects of the special status that they have been given and the aura of mystery they have unfortunately acquired;

The conclusions of the Robertson Panel, as hasty and obviously disinforming as they were, dampened military and government enthusiasm for the study of UFOs. Captain Ruppelt left active duty in August, 1953, and Project Bluebook was turned over to an enlisted man, Airman First Class Max Futch. Additionally, an order called JANAP-146 was issued in December, 1953, which made the reporting of unidentified flying objects by military personnel a National Security Issue, with possible prosecution for its violation. The Air Force was publicly debunking UFOs, while privately drawing a veil of secrecy around their investigations. Personnel changes at Bluebook over the years reflect the decline in interest of the Air Force.

In March of 1954, Major Charles Hardin was put in charge of Project Bluebook, and the 4602nd Air Intelligence Service Squadron began training as field investigators. In 1955, the results of the Battelle Memorial Institute study were finally released as Bluebook Special Report Number 14. The study had a number of flaws, and concluded that improved methods of investigation and reporting would result in all UFO sightings being explained as ordinary phenomena.

In April, 1956, Captain George T. Gregory took over the helm of Bluebook and he began a concerted effort to “explain” every sighting, even if he had to make wide stretches to fit a sighting into an “explained” category.

In July, 1957, the 4602nd Air Intelligence Service Squadron was disbanded, and the 1006th AISS took over investigation duties. In July, 1959, investigative responsibilities were passed on again, to the 1127th Field Activities Group.

In October, 1958, Gregory was replaced by Major Robert J. Friend. By this time, the Air Force considered Project Bluebook to be a burden, and tried to find a way to either transfer it out of the intelligence section or to close it down altogether.

In 1963, Friend was replaced by Major Hector Quintanilla. Bluebook personnel had dropped to just two:, Quintanilla and an enlisted man.

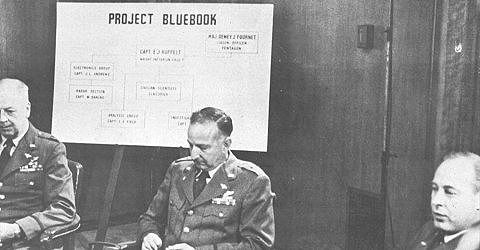

Bluebook Staff Photo

The death knell for Project Bluebook was heard in April, 1966, when the House Armed Services Committee recommended that the Air Force contract with a University for a scientific study of UFOs. On October 7, 1966, the Air Force announced that a program to study UFOs would be conducted by the University of Colorado and headed by Dr. Edward Condon. In reality, the Condon Committee, as it was called, had one task, and that was to provide a reason for the Air Force to end its official investigation of UFOs.

A speech given at the Corning Glass Works by Dr. Condon soon after the study began is revealing:

“It is my inclination right now to recommend that the government get out of this business. My attitude right now is that there’s nothing to it.” “…but I’m not supposed to reach a conclusion for another year.”

That final conclusion of the “Condon Report”, released 9 January, 1969 was:

Our general conclusion is that nothing has come from the study of UFOs in the past 21 years that has added to scientific knowledge. Careful consideration of the record as it is available to us leads us to conclude that further extensive study of UFOs probably cannot be justified in the expectation that science will be advanced thereby.

On December 17, 1969, Project Bluebook was closed and the veil of secrecy had been completely drawn around whatever investigation of UFOs was being conducted by the military.