The so-called “Pentacle Memorandum” convinced UFO researcher Jacques Vallee that the US government had been toying with the official UFO investigations, and that these were a front for something else… if not something more sinister.

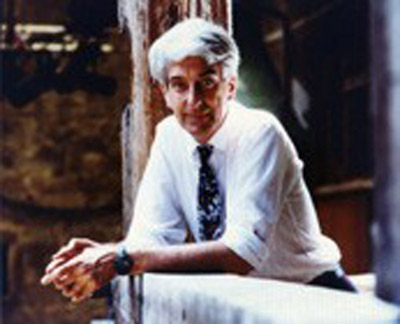

Philip Coppens

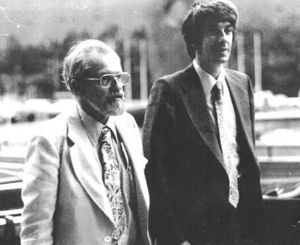

In Forbidden Science (1992), Jacques Vallee, who was the inspiration for one of the main characters in Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, reports how in 1967 he found Allen Hynek’s UFO files to be in serious disarray.

On Sunday, June 18, 1967, Vallee tried to restore some order in the files and “found a letter which is especially remarkable because of the new light it throws on the key period of the Robertson Panel and of Report #14”. This was the report that was also at the core of Leon Davidson’s inquiries and which made him conclude that the US government were using UFOs as part of a psychological warfare exercise.

Jacques Vallee

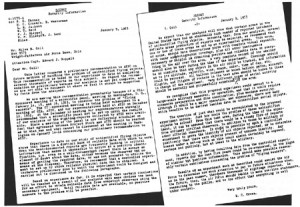

The report Vallee found was stamped, in red ink: “SECRET – Security Information” and dated January 9, 1953. Vallee has nicknamed the man who signed it “Pentacle”, arguing it was not up to him to reveal his name. Since, others have named Pentacle. What was never withheld was that the memo was addressed to Miles E. Coll at Wright Patterson Air Force Base, for transmittal to Captain Ruppelt, the government’s lead investigator – as far as the public was concerned – on UFOs.

Vallee read how the opening paragraph established that prior to the top-level 1953 Robertson Panel, somebody had analysed thousands of UFO cases on behalf of the US government. The document noted that the majority of these case reports were found lacking in several aspects, and that the panel should thus ideally be postponed. Failing such postponement, a list had to be created about what the five specialists that would serve on the panel could and should not discuss.

To quote Vallee: “the representatives of this top-level research group were against convening the Robertson Panel!”

But in the end, they could not stop the formation of the panel, which was chaired by HP Robertson, physicist from California Institute of Technology and would go down into history as “the Robertson Panel”. The other four members were Luis Alvarez, Nobel prize in physics; Lloyd Berkner, space scientist; Sam Goudsmit, nuclear physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory and Thornton Page, astronomer.

When Vallee read the memorandum, he noticed that there

were references to a Project Stork, which Vallee had not

come across before. The project seemed to be a key determinant

in what the panel could discuss – and what not, i.e. what

would be kept away from the panel. By preselecting the evidence,

the conclusion the scientists would reach could thus be

known in advance. It is a well-established practice that

is employed in all government enquiries, but which continues

to bedazzle the public, who realise the commission’s conclusions

are never in line with the truth. This is largely not the

fact of the commission, but of the evidence the commission

is presented with. If you do not get to see a smoking gun,

you can you comment on it?

Of more interest was that the project Stork team had identified

pockets of high UFO activity and recommended that these

should be specifically studied. But they also added that

many different types of aerial activity should be secretly

and purposefully scheduled within the area. To quote Vallee:

“what these people were recommending was nothing less than

a carefully calibrated and monitored simulation of an entire

UFO wave.”

Allen Hynek

Upon reading this memo, Vallee drew the conclusion that the scientists on the panel – and the UFO community as a whole, if not the public as a whole – had been led down a path that had been carefully constructed by people behind the scenes. He wondered what kind of game was truly being played and whether this was just one bad apple or just the tip of the iceberg.

Though just one document, it was a hot potato. Vallee recalled how “Hynek once assured me that if it ever turned out that a secret study had been conducted, the American public would raise an unbelievable stink against the military and Intelligence community. It would be an outrage, he said, an insult to the whole country, not to mention a violation of the most cherished American principles of democracy. There would be an uproar in Congress, editorials in major scientific magazines, immediate demands for sanctions.” The memo clearly

showed that a secret study had been conducted… so how would Hynek and the public react?

Before showing it to Hynek, Vallee shared the memo with a colleague, Fred Beckman, who agreed that the document clearly showed that and in what manner the Robertson Panel had been manipulated. Vallee considered this to be the greatest implication of the memo: the document proved that the Robertson panel had been manipulated, which “amounted to a scandal of major proportion in the eyes of any scientist. […] Here is a special meeting of the five most eminent scientists in the land, assembled by the government to discuss a matter of national security. Not only are they not made aware of all the data, but another group has already decided ‘what can and cannot be discussed (Pentacle’s own words!)’ when they meet.”

Should Vallee show it to Hynek? He drew the conclusion that

Hynek had been “too much timid. In many cases he even believed

in the explanations he was producing.” Vallee decided instead

to sound Hynek out first. On Monday July 10, 1967, Hynek

and Vallee were discussing a new contract that Hynek was

supposed to sign; it would continue his relationship as

one of the main consultants on the government’s UFO programme.

What was remarkable was that the contract was not with the

Air Force, but with Dodge Corporation, a subsidiary of McGraw-Hill,

a textbook publisher. Vallee noted that the contract had

Hynek report into a certain “Sweeney” and that the advice

was on whether UFOs represented a danger for the security

of the US – which in itself is not a scientific question,

which was apparently what Hynek was hired to answer.

Vallee specifically noted that the project Hynek was working

for was not called Blue Book – the official Air Force title

of the project – but Golden Eagle. Vallee asked whether

that name had always been used, and if not, under what name

the project was known before. Hynek dropped the bomb when

he replied its predecessor was called White Stork. (Note

both a bird names and in later years, there would be talk

of an entire “Aviary” as being the secret handlers of the

UFO community in the 1980s.) He then confirmed that in 1953,

he worked for the Battelle Memorial Institute, which had

been responsible for Stork. This meant – and confirmed –

that Pentacle worked for Battelle too. Vallee then asked

whether Hynek knew a Miles E. Coll, to whom the memo was

addressed. Hynek did not. He did name Pentacle and seven

others whose initials appeared in the secret memo. Hynek

confirmed that “they were all administrators or staffers

with Project Stork, including the man who sent me on a clandestine

survey of astronomers in 1952, to find out discreetly what

my colleagues thought of UFOs. ‘Pentacle’ himself was a

leader of Stork.” When Vallee enquired how Stork related

to the Robertson Panel, Hynek replied “practically nil.

Battelle wanted to remain outside all that.” However, that

was clearly not the case – and Vallee knew it. Furthermore,

it was known that it was Battelle that had written Report

#14, a report that was directly linked with the panel. Hynek

was either not sufficiently informed or downplayed the role

of Battelle. Vallee realised Hynek was not lying; he might

just not want to face the overall implication.

Throughout the summer, Vallee battled with the question

whether or not he should show Hynek the Pentacle memorandum.

In August, Vallee asked Hynek to make some enquiries. Could

Hynek have a copy of the Battelle’s card catalogue from

Report #14? Hynek “was coldly told that they were no longer

in existence. Sweeney pretended to be outraged: ‘It’s a

crime, it’s unthinkable…’ But Pentacle is still with Battelle,

and he has told Quintanila that the cards had actually been

thrown away” is what Vallee wrote in his diary.

On September 8, Vallee decided to give, as a parting gift

to Hynek, a framed reproduction of The Lady and the Unicorn.

He decided to insert, between the picture and the cardboard

of the frame, the Pentacle letter. Once Vallee was back

in France, he told Hynek where he could find the memo. In

October, Vallee received a letter from Hynek, who wrote

that he had gone to Columbus to see Pentacle and his team

at Battelle. Rather than a confrontation, he merely told

them about the letter and got – unsurprisingly – rebuffed.

“I quoted enough from memory to get them very worried. They

insisted on the fact that their cards had been destroyed

and there was no listing, and all that had taken place with

the approval of ATIC.”

But Hynek was upset – worried. In March 1968, Hynek reported

that he once again went to see Pentacle, but rather than

a one to one meeting, Pentacle had four colleagues with

him. When Hynek started reading from his notes, Pentacle

snatched the paper out of his hand and said it was an old

story and did not return his notes. Vallee: “Why should

Pentacle worry so much about a simple letter written fifteen

years ago?”

By 1969, it became clear that Hynek would not confront Pentacle, but the people knew that Hynek knew it was a sham, and that he was unhappy about being played – he was, of course, not the only one, but one of those who knew. At the same time, Hynek wrestled with the question whether or not he should go public with the story – which would test his theory that if he did, it would lead to moral outrage with the general public and its elected representatives.

Hynek did eventually talk, though what he said was not what he had found out. Instead, he rather sheepishly argued that a new study should be done. At that moment, the Air Force pushed him aside. Vallee: “First they defused the issue by getting their most vocal opponents to testify before bogus Congressional Hearings; then they selected Ed Condon, a physicist who was about to retire, and he signed his name to a report which was a travesty of science, yet reassured the establishment. They used that report to bring about the liquidation of Hynek’s position, but they were careful not to fire him.” That could, of course, have just been the event that would make Hynek go public.

Though the memo never received the impact Vallee thought it would have from a public point of view , the memo did have an important effect on both Hynek and Vallee; both realised that they had been pawns in a game which they never were able to control, if only because both were too timid to shout “conspiracy” from the rooftops. As late as the 1990s, Vallee still shied away by withholding Pentacle’s name. Vallee concluded that “the discovery of the Pentacle document had a major impact on me. It gave me an uncomfortable insight into the practices of government agencies and the high-powered consultants who serve them. […] It was the main raison for my return to Europe in 1967. It made obvious some unsavoury aspects of scientific policy at the highest level. It provided quite an education for an idealistic

young astronomer.” In short, it shattered his innocence.

Shortly after the publication of Vallee’s book in 1992, a document which purported to be the Pentacle Memo came into limited circulation among certain researchers. Dale Goudie confronted Vallee with the alleged Pentacle memo. On June 12, 1993, Vallee agreed that “the document you sent me appears to be genuine. It corresponds to the one I saw.” The document does indeed contain confirmation that Battelle Memorial Institute was working on UFO project(s) at the time of the Robertson Panel (January 1953), and apparently could exercise some amount of control over the handling of the subject matter.

The document was of interest to the entire UFO problem too. UFO researcher Barry Greenwood pointed out that this was a top secret document. It showed that the government treated UFOs as a cover… but that the report also suggested – because of no references to it – that no extra-terrestrial craft had landed, or crashed. Vallee agreed that “the significance of the memo comes, in part, from what it does not say. In particular, it makes no reference to any recovered UFO hardware, at Roswell or elsewhere, or to alien bodies.”

To anyone who still failed to see the importance of the 1955 memorandum, Vallee added that “the Pentacle proposal goes far beyond anything mentioned before. It daringly states that ‘many different types of aerial activity should be secretly and purposefully scheduled within the area’. It is difficult to be more clear. We are not talking simply about setting up observing stations and cameras. We are talking about large-scale, covert simulation of UFO waves under military control.”

Vallee knew, however, that this gigantic revelation – that

the US government had made a policy, which it most likely

then executed – that UFO waves were fabricated, would go

over both UFO researchers and the public head. It is like

finding out that Santa Claus does not exist. He lamented

that “I find it odd that a [UFO] group […] should fail to

see the significance of the Pentacle Memo, which is an authentic

document, when so much time, money and ink have been devoted

over the last several years to an in-depth analysis of the

MJ-12 papers, which were faked. Perhaps the Pentacle memo

only proves that scientific studies of UFOs (and even their

classified components) have been manipulated since the fifties.

But it also suggests several avenues of research which are

vital to the future of this field: why were Pentacle’s proposals

kept from the panel? Were his plans for a secret simulation

of UFO waves implemented? If so, when, where and how? What

was discovered as a result? Are these simulations still

going on?” They are big questions… which the UFO researchers

do not want to hear… and which no-one can answer…

SECRET

SECURITY INFORMATION

G-1579-4

cc: B. D. Thomas

H. C. Cross/A. D. Westerman

L. R. Jackson

W. T. Reid

P. J. Rieppal

V. W. Ellsey/R. J. Lund January 9, 1953

Files

Extra [handwritten]

Mr. Miles E. Coll

Box 9575

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio

Attention Capt. Edward J. Ruppelt

Dear Mr. Coll:

This letter concerns a preliminary recommendation to ATIC

on future methods of handling the problem of unidentified

aerial objects. This recommendation is based on our experience

to date in analyzing several thousands of reports on this

subject. We regard the recommendation as preliminary because

our analysis is not yet complete, and we are not able to

document it where we feel it should be supported by facts

from the analysis.

We are making this recommendation prematurely because of

a CIA-sponsored meeting of a scientific panel, meeting in

Washington, D.C., January 14, 15, and 16, 1953, to consider

the problem of “flying saucers”. The CIA-sponsored

meeting is being held subsequent to a meeting of CIA, ATIC,

and our representatives held at ATIC on December 12, 1952.

At the December 12 meeting our representatives strongly

recommended that a scientific panel not be set up until

the results of our analysis of the sighting-reports collected

by ATIC were available. Since a meeting of the panel is

now definitely scheduled we feel that agreement between

Project Stork and ATIC should be reached as to what can

and what cannot be discussed at the meeting in Washington

on January 14-16 concerning our preliminary recommendation

to ATIC.

Experience to date on our study of unidentified flying

objects shows that there is a distinct lack of reliable

data with which to work. Even the best-documented reports

are frequently lacking in critical information that makes

it impossible to arrive at a possible identification, i.e.

even in a well-documented report there is always an element

of doubt about the data, either because the observer had

no means of getting the required data, or was not prepared

to utilize the means at his disposal. Therefore, we recommend

that a controlled experiment be set up by which reliable

physical data can be obtained. A tentative preliminary plan

by which the experiment could be designed and carried out

is discussed in the following paragraphs.

Based on our experience so far, it is expected that certain

conclusions will be reached as a result of our analysis

which will make obvious the need for an effort to obtain

reliable data from competent observers using the [… unreadable…]

necessary equipment. Until more reliable data are available,

no positive answers to the problem will be possible.

Mr. Miles E. Coll -2- January 9, 1953

We expect that our analysis will show that certain areas

in the United States have had an abnormally high number

of reported incidents of unidentified flying objects. Assuming

that, from our analysis, several definite areas productive

of reports can be selected, we recommend that one or two

of theses areas be set up as experimental areas. This area,

or areas, should have observation posts with complete visual

skywatch, with radar and photographic coverage, plus all

other instruments necessary or helpful in obtaining positive

and reliable data on everything in the air over the area.

A very complete record of the weather should also be kept

during the time of the experiment. Coverage should be so

complete that any object in the air could be tracked, and

information as to its altitude, velocity, size, shape, color,

time of day, etc. could be recorded. All balloon releases

or known balloon paths, aircraft flights, and flights of

rockets in the test area should be known to those in charge

of the experiment. Many different types of aerial activity

should be secretly and purposefully scheduled within the

area.

We recognize that this proposed experiment would amount

to a large-scale military maneuver, or operation, and that

it would require extensive preparation and fine coordination,

plus maximum security. Although it would be a major operation,

and expensive, there are many extra benefits to be derived

besides the data on unidentified aerial objects.

The question of just what would be accomplished by the

proposed experiment occurs. Just how could the problem of

these unidentified objects be solved? From this test area,

during the time of the experiment, it can be assumed that

there would be a steady flow of reports from ordinary civilian

observers, in addition to those by military or other official

observers. It should be possible by such a controlled experiment

to prove the identity of all objects reported, or to determine

positively that there were objects present of unknown identity.

Any hoaxes under a set-up such as this could almost certainly

be exposed, perhaps not publicly, but at least to the military.

In addition, by having resulting data from the controlled

experiment, reports for the last five years could be re-evaluated,

in the light of similar but positive information. This should

make possible reasonably certain conclusions concerning

the importance of the problem of “flying saucers”.

Results of an experiment such as described could assist

the Air Force to determine how much attention to pay to

future situations when, as in the past summer, there were

thousands of sightings reported. In the future, then, the

Air Force should be able to make positive statements, reassuring

to the public, and to the effect that everything is well

under control.

Very truly yours,

[unsigned]

H. C. Cross

HCC:??