Editor’s

Note: Robert A. Galganski has a master’s degree in civil engineering and is employed as a ground vehicle crash safety systems research and development specialist. He received the Ufologist of the Year award at the 1997 National UFO Conference in Springfield, Ohio, for his contributions to Roswell Incident research.

Article from the International UFO Reporter, Summer 1998, Volume 23, Number 2.

An Engineer Looks at the Project Mogul Hypothesis

by Robert

A. Galganski

In early July 1947, Mac Brazel, foreman of the Foster sheep ranch northwest of Roswell, New Mexico, discovered a large quantity of extremely unusual, widely scattered, and highly fragmented lightweight debris on a pasture. The Army initially attributed it to the misidentified remnants of a downed weather balloon and an attached radar target. Forty-seven years later, the Air Force explained the debris as similar wreckage from a top-secret Project Mogul balloon train.

More than three years have passed since I first examined the debris-field issue quantitatively in “The Roswell Debris: A Quantitative Evaluation of the Project Mogul Hypothesis,” IUR, March/April 1995. This article updates my initial research.

The debris field

Most of the debris consisted of lightweight, thin-gage, flat or slightly curved, sheet like fragments

exhibiting physical properties atypical of late-1940s technology. There appears

to have been two distinct types at the site: (1) foil-like pieces easily crumpled

by hand which completely recovered their original shape and showed no signs

of wrinkling when released; and (2) pieces which could not be deformed

or damaged by any means, even when whacked with a 16-pound sledgehammer. I refer

to both kinds of debris, which would not burn, as thin-shell material. (Common

thin-shell products—which do not possess such extraordinary deformation

characteristics—include Saran wrap, balloon film, aluminum foil, and motor-vehicle

and aircraft body panels.)

Major Jesse Marcel, intelligence officer of the 509th Bomb Group based at Roswell Army Air Field

(RAAF), inspected the site shortly after Brazel reported the debris to the Chaves

County sheriff in Roswell. Marcel described a big field: debris “.

. . about as far as you could see—three quarters [of a] mile long and two

hundred to three hundred feet wide.” It was “scattered all over—just

like you’d explode something above the ground and [it would] just fall

to the ground.” The shortest pieces were “four or five inches. It

was [as if it were from] something of some greater area that had been together.”

A rectangular field shape is implicit—but by no means certain—in Marcel’s description.

For that configuration, the debris would have littered an area equal to 250

ft (average width) x 4,000 ft (about ¾ of a mile) long = 1,000,000 ft2 (nearly 23 acres).

Methodology for quantitatively evaluating the Mogul hypothesis

Evaluating the Mogul hypothesis quantitatively constitutes a three-step process.

- Estimate the quantity of unusual thin-shell material on the field.

- Determine the quantity of material(s) contained in a Mogul balloon train that could have been the source of the extraordinary debris.

- Compare the two numbers. The comparison provides a numerical indication of how good—or how bad— the Mogul explanation is.

To carry out the first step in the evaluation process, I had to formulate a mathematical model of the debris field. Its development is detailed in my 1995 IUR article, but a brief description is provided below.

Debris-field model

The debris-field model uses surface area to estimate the quantity of unconventional thin-shell material on the Foster ranch. Surface areas of other debris forms that covered significantly less of the field are neglected.

To simplify the analysis, the field is represented mathematically as a flat plain with flat shell fragments distributed over it in a variable, two-dimensional pattern. One very small region near one (the presumed front) edge of the field is assumed to have a moderately dense debris concentration—20% ground coverage. (The actual site must have featured at least one, fairly large region of closely packed debris because the sheep refused to cross it; they had to be driven around it.) The density drops off rapidly away from this location, exhibiting an extremely spotty coverage over the rest of the simulated pasture.

The unknown debris distribution is approximated by equations which attempt to simulate the major

elements contained in the most reliable first-statement, firsthand, and

secondhand witness testimony. My objective was to generate a conservative approximation of that pattern—one that would estimate the smallest possible amount of on-ground thin-shell material—to minimize the risk of

unfairly biasing the evaluation outcome against the Mogul hypothesis.

Consistent with that approach and for additional reasons discussed in the 1995 article, I selected a parabola instead of a rectangle as the most plausible debris-field shape. The model’s parabolic field has the same overall dimensions described by Major Marcel: 250 feet wide (at its far end) by 4,000 feet long. But it encompasses only 667,000 ft2 (about 15 acres) of pasture, 33% less ground area than that contained in the rectangular configuration.

Initial evaluation: Mogul Flight 9

In the fall of 1994 the Air Force posited that Mogul Flight 4 was the source of the debris

on the Foster ranch. That explanation seemed so improbable I applied my newly

developed model to a different balloon train, Flight 9. Researcher Karl Pflock,

in his 1994 monograph, Roswell in Perspective, speculated that the debris

was merely polyethylene (plastic) balloon fragments from downed balloons comprising

that aborted experiment. My analysis showed that if all the balloons in Flight

9 had landed and shredded at the site, nearly four such trains would be needed

to generate enough debris to litter 15 acres of ranch land.

Then, in his 1997 book UFO Crash at Roswell: The Genesis of a Modern Myth, coauthor and former Mogul project engineer Charles B. Moore revealed that Flight 9 actually used neoprene (synthetic rubber) balloons. Since Flight 9 was thus eliminated as a candidate debris-field causative agent, I took another look at the Flight 4 hypothesis.

Updated evaluation: Mogul Flight 4

According to Charles Moore, Flight 4 consisted of 28 neoprene, meteorological-sounding (i.e., weather) balloons attached to a 600-foot-long master line of braided nylon cord, three ML-307B rawin radar targets, possibly one or more silk-canopy parachutes, and a variety of test equipment such as a sonobuoy microphone, radio transmitter, dry cells, and plastic containers holding solid and liquid ballast. All components and systems were ordinary off-the-shelf items; only the Mogul program objective was classified.

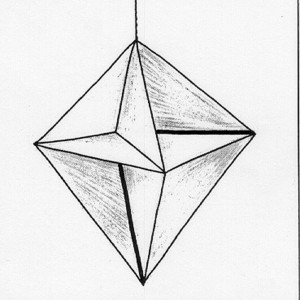

|Fig. 1. Drawing of a rawin radar target used in some |Project Mogul balloon train launches, including |Flight 4.

A possible debris deposition scenario.

It’s absolutely inconceivable—to me and many other Roswell researchers, anyway—that anybody could have mistaken pieces of neoprene balloon film (either in its brand-new flexible and tan-colored condition or its brittle, dark-colored, and sun-deteriorated state) and silk fabric for either one of the two highly unconventional shell-like materials described earlier. By the process of elimination, that leaves the radar targets as the only possible Flight 4 source for the thin shell fragments found at the site.

The rawin targets. Figure 1 presents a drawing of a rawin radar target. According to Moore

(personal correspondence dated March 31, 1995), “These targets consisted of nine right-triangular segments with 24-inch-long bases and heights. Each segment consisted of a panel of aluminum foil laminated to some fairly tough, heavy-duty paper and deployed on balsa wood struts.” (Moore is also on record saying that the struts were coated with glue to stiffen and render them noncombustible.)

Moore recently told Roswell researcher Robert J. Durant that each target was constructed of only seven triangular segments having the same dimensions given above. I elected to use nine triangles—yielding a single-target surface area of 18 ft2—in order to maximize the total amount of Mogul-supplied thin-shell material. This gives the benefit of the doubt to—and helps—the Mogul hypothesis.

Gut feeling. The reported amount and physical characteristics of the highly fragmented debris, along with its widespread distribution at the ranch site, is inconsistent with wreckage that could have come from a Mogul balloon train.

Figure 2 presents an official July 8, 1947, Army photo of (primarily) rawin radar target wreckage. How anybody could have mistaken the badly wrinkled and torn aluminum foil/paper laminate—white paper can be seen peeling away from the foil!—and broken balsa-wood sticks for the allegedly extraordinary debris is beyond comprehension.

A recent series of experiments proved that the thin-strut fragments found at the site were not glue-coated balsa-wood sticks from radar targets (see “The Glue Explanation Just Won’t Stick,” IUR, Winter 1997–98). It follows that the unusual thin-shell material also found there was something other than the metalized paper used in target construction.

Common sense, logic, a massive body of corroborative anecdotal evidence, and limited but fundamentally sound and persuasive empirical data and observations lead to an inescapable conclusion: Mogul Flight 4 was not responsible for the debris field.

___________________________________

Fig. 1. Drawing of a rawin radar target used in some Project Mogul balloon train launches, including Flight 4.

A quantitative assessment.

The quantitative evaluation methodology outlined earlier will now be applied to Mogul Flight 4. The objective: Ascertain if there was enough thin-shell material in that balloon train to account for the reportedly unusual shell-like stuff on the Foster ranch site. As noted previously, the radar-target laminate—aluminum foil bonded to paper—was the only possible source for that type of material.

Let Area 1 denote the model-estimated surface area of on-ground, thin-shell debris. This parameter, calculated in my initial study (and still applicable), is equal to 6,880 ft2.

To give the Mogul hypothesis a fighting chance, assume that all three targets landed on the pasture and were broken apart and shredded into pieces of varying size. The total laminate surface area (Area 2) is equal to 3 targets ´ 18 ft2 / target = 54 ft2.

Compare the two surface areas by dividing Area 1 by Area 2. We obtain 6,880 ft2 ¸ 54 ft2 = 127.4. This number tells us that it would take more than 127 Flight 4 balloon trains — more than 381 radar targets — to litter the field! Mercy.

Model accuracy. Obviously we can’t validate the accuracy of the above finding. But a crude, indirect measure of the model’s simulation capability can be defined: C—the overall debris coverage ratio. This parameter is equal to the total model-generated surface area of on-ground, thin-shell material fragments divided by the total field ground area. A reasonably accurate model will have a C value roughly similar to that which could (theoretically) be computed for the actual site.

We can safely assume that the Foster ranch debris field consisted of mostly open range, with individual pieces or clusters of debris scattered over it. Since there had to be sufficient thin-shell material available to create at east one densely packed region as well as to define the perimeter of the vast area described by Marcel, a value of C between 0.01 and 0.10—i.e., between one to ten percent coverage—appears reasonable.

The model’s debris coverage density is 6,880 ft2 ¸ 667,000 ft2 = 0.0103 (1.03% overall coverage)—at the lower end of the arbitrary acceptable range. Nearly 99% of the simulated field is debris-free or uncovered, confirming the desired conservative nature of the model.

Summing up. My mathematical analysis indicated better than a two order-of-magnitude disparity between the amount of thin-shell material on the ground (by all accounts—a lot) and what Mogul Flight 4 could have supplied (very little). This enormous difference provides a comfortable margin for error. For example, even if the model’s surface-area estimate is off (too high) by a factor of 10, it would still require nearly 13 balloon trains (via 688 ft2 ¸ 54 ft2) or 39 targets to generate the shredded shell fragments found at the site.

Still think that a single balloon train caused the Roswell debris?

Gigo?

Roswell detractors might say that my analysis is flawed because decades-old eyewitness testimony is factored into the debris-field model. Because Major Marcel’s large field-size

estimate constitutes a vital input to the model, it is a likely target for critics.

They might claim that he grossly overestimated the field size, resulting in a classic case of GIGO—garbage input (a grievously poor field-area estimate) generating garbage output (the 127-plus-balloon train result). The merits of this charge can be checked out by doing simple what-if analysis.

| Table 1. What-if Analysis for the Only Possible (and Highly Suspect) Mogul Flight 4 Debris-deposition Scenario

|

|||||||||||

| (ft2) | (acres) | ||||

| 4,0002,000

1,000 250 |

667,000333,000

167,000 41,700 |

15.37.6

3.8 1.0 |

6,8803,500

1,810 540 |

127.464.8

33.5 10.0 |

0.81.5

3.0 10.0 |

Notes: (1) N is the number of Flight 4 balloon trains needed to litter the field with radar target laminate. N = M/R, where R = 54 ft 2 is the total laminate surface area comprising three rawin radar targets. (2) P = ( R/M )100% is the percentage of on-ground, thin-shell debris that a single Flight 4 (three radar targets) can account for.

What-if analysis for the Mogul Flight 4 hypothesis

Assume that Major Marcel overestimated the length of the debris field. The effects of such an error on the model’s output and associated hypothesis evaluation outcome are examined by varying the length of its parabola-shaped field.

Calculations and commentary. Table 1 presents the results of the analysis for several

field lengths ranging from Marcel’s 4,000-foot estimate to 250 feet. The width of the field is held constant (at 250 feet) for the sake of simplicity.

Figure 3 illustrates the relative sizes of the four field lengths considered.

Table 1 lists the field ground area A and the amount of thin-shell material M on it (columns two and three, respectively) for each field length L considered (column 1). The fourth column shows the number of Mogul Flight 4 balloon trains N needed to supply the thin-shell material for each parabola consistent with the model-predicted surface area (see note 1 beneath the table). Finally, the last column lists values of P (the inverse of N); it tells us what percentage of the model-estimated surface area one balloon train could have supplied (see note 2).

If the field was only half as long as Marcel thought it was, N decreases from more than 127 to about 65 while P increases from 0.8 to 1.5. If he erred by a factor of four (i.e., L = 1,000 feet)—a seemingly high but possible error—N decreases to more than 33 while P rises to only 3.0%. These results indicate that a significantly error doesn’t help the Mogul hypothesis very much. smaller field within the range of possible human

Figure 3. Relative sizes of the parabolic debris fields examined in the what-if analysis. Each parabola is 250 feet wide at its far end.

The smallest length listed in Table 1—250 feet —assumes that Marcel completely butchered his estimate, imagining the debris to be scattered over an area 16 times longer than it actually was. Even for this mind-numbing scenario—a pasture with

less area than a football field—it would still take 10 Mogul Flight 4 launches to supply the thin-shell material found on the ground. Alternatively, one Mogul train would account for only 10% of the debris.

One final note. The Air Force claimed in its 1994 report that the debris was strewn over a circular area 200 yards (600 feet) in diameter. (A July 9, 1947, story in the Roswell Daily Record, attributed to an interview with Mac Brazel in the newspaper’s office, is the basis for that contention.) My model cannot simulate a circular debris field, so we can’t evaluate the Mogul hypothesis for this pattern using a model-generated M value in the methodology employed above. However, we can make a ballpark-type estimate using information provided in Table 1.

The table shows that a 2,000-foot-long parabola has an area of 333,000 ft2—just 18% more than the 283,000 ft2 in a 200-yard-diameter circle—and that it would take nearly 65 Flight 4 balloon trains to deposit debris over that narrow strip of land. The number of Mogul balloon trains required to deposit enough thin-shell material to outline the perimeter of a 200-yard-diameter area can be crudely approximated by scaling that number using the ground area ratio of the two field shapes. We get (283,000 ft2 / 333,000 ft2) ´ 65 = 55 balloon trains—admittedly a very rough estimate. However, its double-digit magnitude—and attendant large allowable margin for error—indicates that even the Air Force’s own explanation doesn’t fit the Mogul hypothesis.

Reduced-size field coverage ratios. Using the terms defined in Table 1, the previously

discussed field coverage ratio can be expressed as C = M / A. C corresponding to field lengths L = 2,000, 1,000, and 250 feet is equal to 0.0105, 0.0108, and 0.0129, respectively, indicating that the smaller fields are also about 99% debris free. The values of N and P listed in Table 1 are thus—at the very least—reasonable first-approximation type estimates.

Summary and conclusion

A mathematical model idealized the debris field as a variable-length, parabola-shaped region sparsely covered with fragments of an extraordinary thin-shell material.

It was assumed that Mogul Flight 4 created the debris field, leaving behind metalized-paper, rawin-radar-target remnants having a known total surface area.

Model-predicted and Mogul Flight 4-supplied thin-shell material surface areas were compared. One Mogul balloon train could account for only an extremely small fraction of the reported debris, even if Major Jesse Marcel had badly overestimated the field size.

Clearly, Project Mogul Flight 4 could not have been responsible for the debris found on the Foster ranch. Indeed, the analysis illustrates in a most compelling fashion just how absurd the Air Force’s Mogul hypothesis really is.