Chapter 1

The Stage is Set

Barely 59 months after the Japanese signed an unconditional surrender on September 2, 1945, a relatively minor civil war broke out on the Korean Peninsula between the Democratic Republic of (South) Korea and the communistic Democratic People’s Republic of (North) Korea. Some historians point out that what started as a civil war limited to a then third rate economic and strategic nation; escalated rapidly into an undeclared training ground for new weapons systems, advanced strategic planning, and armed forces drawn from more than seventeen other nations fighting on the side of freedom and democracy. The enemy comprised two nations (North Korea, Red China) with the Soviet Union standing in the background, supplying training personnel and materiel. Many claimed that the Korean conflict was only an inevitable consequence of the larger “cold war” that was raging between America and the Soviet Union.

America’s real military strategy in Korea was “…to ensure that it did not grow into World War 3. This meant that political leaders (in Washington) were in charge of the war strategy rather than the military leaders (in the field).” (Anon., pg. 3-38, 1986).

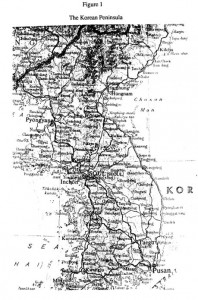

The Korean peninsula (see Figure 1) was supposed to become an independent nation during WW2 (according to the superpowers United States, Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France). “When the war with Japan was over, there were no US troops in Korea. Since it would take some time to move troops into the peninsula, the United States asked that the Soviets accept the surrender of all Japanese troops north of the 38th parallel in Korea and the United States all those south of the parallel. The division was supposed to be a temporary measure, but the Soviets began to treat it as a permanent boundary, and they took control of North Korea. The Soviets did not want to see Korea become a free nation and come under Western influence.” (Anon, 1986)

But our concern is not so much with politics as it is with the state of advanced warfare technology at this time. What did the United States Air Force have in its arsenal during this war? What were the Russians flying? Were there other nations with advanced flying craft that did not have wings but could fly higher and faster than anything either the Russians or the Americans had? The answer is a simple NO!

Of special note is the fact that recently uncovered, seemingly authentic U.S. government documents have indicated that our government had in its possession at least one highly advanced spacecraft not from this planet which was allegedly recovered in 1947 in New Mexico (note 1). If this is true and scientists had succeeded in understanding how to duplicate its advanced technology, then some or all of the UFO reports coming from Korea could represent an American technological development.

Then one would have to ask:

(1) why these disks were not used in a more aggressive way to help win the war,

(2) why these disks never crashed or were never recovered by anyone,

(3) why our Air Force has continued to spend millions of dollars (since the Korean war) on turbo-jet engines and swept-wing airplanes rather than on self-propelled metallic-surfaced oblate spheroid (discs), and

(4) why we have seen no UFO like aerial objects fighting in the Viet Nam war to help the U.S. forces win. If the aerial objects to be described are not American, Soviet, or from another nation on earth then an intriguing possibility exists; viz., they represent an alien technology.

One of the interesting things about the Korean “Conflict” as it was called at the time was the role played by the world’s two super powers, each supplying their respective surrogate Korean armies in the field, at least until November of 1950 when soldiers and materiel from Communist China flooded across the Yalu River into North Korea. What had started out as a localized peace keeping action by United Nations troops suddenly presented the spectre of all-out war with China, the most populous nation on the earth. A nuclear sword swung tenuously above both sides of the conflict.

The Soviets had largely equipped North Korea’s army and its air force. It was, perhaps, partly a field training exercise for them to see how well their planes and tanks, their ammunition and other war materiel would fare in the extremely cold weather and in the hands of less well trained soldiers. On June 25, 1950 the North Koreans had flooded across the 38th parallel, the former boundary with their cousins to the south, and quickly overran the smaller and less well prepared South Korean units. With the Soviet delegate voluntarily absent, the United Nations Security Council in New York City invoked military sanctions against North Korea (June 27, 1950) and formally requested its member states to give whatever aid they could to South Korea. The die had been cast.

Poured into this already fiery hot mold were soldiers from the following countries:

- United States of America

- Australia

- Belgium

- Luxembourg

- Canada

- Columbia

- Ethiopia

- Great Britain

- Greece

- Italy (not a U.N. member)

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Philippines

- South Africa

- Thailand

- Turkey

Many hundreds of thousands were to be maimed or killed in the fray. The mold was severe and unforgiving as it is in any war to those who must do the fighting. A total of 25,604 U.S. servicemen were killed in this “conflict” with another 137,051 listed as casualties. South Korea lost 415,004 soldiers with more than 1,312,800 casualties. The other U.N. participating nations lost 3,094 men with over 16,500 casualties. It has been estimated that the communist’s casualties were about two million (Morse, vol. 15, 1969).

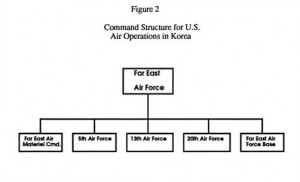

The free world’s armed forces were unified under United Nations command. It was headed by General Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief, Far East Command (FECOM). General MacArthur reported to the Joint Chiefs of Staff concerning all of the U.S. forces (Momyer, 1978). Figure 2 illustrates the command structure for U.S. air operations in Korea in 1950. What it doesn’t show is General MacArthur’s failure to establish an army component command since “He reserved to himself the roles of the Far East Command structure.” (Ibid., pg. 53)

Both the U.S. Navy and Air Force set up respective components named the Naval Forces Far East and Far East Air Force commands, respectively. Both had staffs manned so as to direct their respective forces throughout the area of MacArthur’s responsibility. Whether or not this short-coming (not having a balanced staff represented by all of the armed services) contributed to how UFO sighting reports were handled remains to be seen.

The U.S. Navy’s Task Force 77 operated off the Eastern coast of Korea in the Sea of Japan with its aircraft carriers providing interdiction of enemy aircraft, bombing support, and close air support for Marine operations up to 70 miles inland along the entire length of North Korea’s coast.

Reference to Figure 2 shows that the Commanding General of the 5th Air Force was located in Korea and exercised operational control of Marine aircraft as well as coordinating bomber strikes with all other forces such as flak suppression and fighter support.

U.S. Air Power During the Korean War:

But what about the Air Force participants? Who were they? What units were called up for service so soon after the Second World War had ended? The Far East Air Force (FEAF) consisted of these units

- 5th Air Force

- 13th Air Force

- 20th Air Force

- Far East Air Materiel Command

- The Far East Air Force Base

The Far East Air Force Command (FEAF) was under the command of Lieutenant General George E. Stratemeyer (1890-1969). On October 8th, 1950 he requested that he be given full operational control of all air units. This meant that he would be able to fully coordinate the Air Force’s mission with those of other ground forces; even specifying the amount of forces to be deployed, the type of munitions, the time on and off targets, and the controlling agencies.

FEAF chose all their targets (both for the Air Force and Naval carrier-based aircraft) by means of a “targeting committee” that was composed of Navy and Air Force representatives. This coordinated approach had proven itself in North African air operations where there were little or no industrial targets and other targets required less force to destroy or neutralize.

As indicated above, the 5th Air Force was coordinated by the Far East Bomber Command and, in turn, coordinated fighter escort. Air route planning to and from targets was the joint responsibility of the 5th Air Force and Far East Bomb Command. B-29 bombers were used extensively during the war (Figure 3). The Far East Bomber Command consisted of three B-29 groups drawn from the Strategic Air Command (SAC).

Following are different airplane models flown by U.S. pilots during the Korean War: (Maximum speed [mph] is given in brackets)

- F-80 (Shooting Star) [543]

- F-84 (Thunder jet) [622]

- F4U-4B (Marine) [450] (see Figure 9)

- F7F-3N [427]

- F9F-2 (Panther jet) (note 2) [625] F-94 [600] (see Figure 7)

- AD Skyraider (Navy, propeller-driven aircraft) (note 3) [320]

- P-51 (Mustang) [370]

- F-86 (Sabrejet) [680] (see Figure 4)

- T-6 [205] (see Figure 10)

- B-26 (2 engine bomber) [282]

- B-29 (4 engine heavy bomber) [358] (sec Figure 3)

- C-54 (troop transport) [274] (see Figure 8)

Figure 3

B-29 Bomber in Flight

(Reproduced by permission of the National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution)

The F-100 Super Sabre flew for the first time in 1953 but was not used in the Korean War.

North American Aviation’s all-weather F-86 Sabrejet was the nearest combat fighter America had to the MiG-15 in most operational respects. It was the “…best aircraft the U.S. had during the Korean War” (Anon., pg. 3-41, 1986). It was 41 feet long with a wing span of 37′ 1″. Its loaded weight was 16,500 pounds. The F-86 had a maximum speed of over 660 mph and a service ceiling of about 50,000 feet. Its armament consisted (model E) of six 50 cal. machine guns in the nose. There also were provisions for 16-127mm rockets under the wings and two each 1,000 pound bombs or two each 2,000 pound bombs in lieu of auxiliary fuel tanks. Three prototypes were ordered in May 1945; the XP-86 flew for the first time on October 1, 1947.

Figure 4

F-86 Sabre Jet

(Reproduced by permission of the National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution)

In November 1950 the 4th Fighter Interceptor Group arrived in Japan with its F-86As and soon operated out of Kimpo air base in South Korea (Jackson, 1979). Regarding air operations, Braybrook (1987) said that F-86s generally “…flew in sections of four aircraft, up to eight sections together, and between 35,000 and 45,000 feet…depending on model. The MiG-15s crossed the border at around 50,000 feet in ‘trains’ of 60 to 80 aircraft.” He goes on to point out that most F-86 kills of Communist aircraft were made without radar; most used a fixed gunsight and approached the enemy from the enemies’ 6 o’clock position.

By the close of the war there were seven U.S. fighter wings in Korea with 297 F-86s and 218 F-84s. Sabre operations peaked at 7,696 sorties in June 1953 and an average of 26 sorties per aircraft for that month (Braybrook, 1987). Sabres destroyed 810 enemy aircraft, 792 of which were MiG-15s. Seventy eight U.S. aircraft were lost.

U.N. airplanes provided air cover for U.N. ground forces. Two weapons in particular proved to be the best new weapons in Korea, napalm and aerial rockets. The rockets had the destructive force of a 105mm cannon shell. Napalm bombs were 110 gallon tanks of jelled gasoline which exploded in fire over an area 250 feet long and 80 feet wide.

What could an American pilot do if he chased a Soviet MiG airplane north over the Red Chinese border? The FEAF commander was given guidance from Washington. So called “hot pursuit” was authorized under some conditions, “…but attacks against aircraft taking off from bases across the Yalu (river) were not.” (Ibid., pg. 56) It is interesting to note that none of the UFO sighting reports presented here includes a “hot pursuit” very far because the unidentified aerial craft almost always outperformed the pursuing jet airplanes.

Soviet Air Power During the Korean War:

This is a list of some of the airplanes flown by the air forces of the North Koreans, the Chinese Communists, and the Soviet Union.

- La-9 (single engine, propeller driven fighter) [430]

- La-11 (single engine, propeller driven fighter) [420]

- Ilyushin 10 (single engine, propeller driven fighter) [300]

- YAK-9 (single engine, propeller driven fighter)

- YAK-15 (single engine, propeller driven fighter)

- MiG-15 (single engine, jet fighter) [680] (see Figure 5)

- TU-2 (bomber) [340]

It is instructive to note that at this time the Soviets had over 15,000 MiG model 15s available (Nowarra and Duval, pg. 168, 1972). Stockwell (1956) estimates the number to be from 12,000 to 15,000. The Red Chinese Air Force supposedly had about 1,000 MiG-15s as they entered the Korean War. This jet fighter interceptor was affectionately code named “Fagot” by N.A.T.O. officials. Braybrook (1987) points out that the number of Communist aircraft peaked at about 1,800 (950 MiGs) with over 400 parked at one airfield in North Korea.

The MiG-15 measured only 36′ 4″ long, with a wing span of 33′ 1″ (Figure 5). It weighed 8,316 pounds empty and could carry a payload of 5,907 pounds in addition to its single pilot. Its gross weight was 11,264 pounds. Its top speed was about 680 mph (Mach limit = 0.89) at sea level and had a service ceiling of 51,000 feet and a range of 1200 miles with underwing fuel tanks. It stalled at (or possessed a minimum air speed of) 109 mph. The MiG-15 carried one 400 rounds per minute, 37mm cannon and two 23mm caliber cannons in addition to two each 990 pound bombs. This fighter entered the war on November 1, 1950 when a flight of six aircraft attacked Air Force Mustangs south of the Yalu River without doing any damage. Soviet units regularly flew combat duty over Korea in conjunction with Chinese Communists and North Korean formations (Jackson, Pg. 94, 1979).

The U.S. Air Force Junior ROTC publication “Aerospace Science: History of Air Power” (Anon., 1986) states that the MiG-15 “…was faster, more maneuverable, could climb faster and higher, and possessed more firepower than the F-80, F-84,or the Navy F-9F(sic) fighters. In fact, the MiG-15 even had the edge, at high altitude, over the F-86 Sabrejets which were the best aircraft the United States had during the Korean War.” Because of superior pilot skill by U.S. pilots, nine MiGs were shot down for every U.S. aircraft.

The La-9 was a Soviet designed and built fighter, code named “Fritz”. It possessed a maximum speed of 430 mph at sea level and a service ceiling of 35,600 feet. Its wing span was 34′ 9″ and was 30′ 2″ long. This piston-driven propellor airplane was in service until the 1948 – 1950 period.

Another Soviet fighter that was used in combat was the La-11, code named “Fang”. It is comparable in design to Republic’s P-47N “Thunder-bolt.” Delivered in early 1946, this single seat fighter interceptor was only 28′ 6.5″ long with a wing span of 31′ 10″. Its top speed was about 420 mph with a service ceiling of about 34,000 feet. It flew in Korea with Chinese and North Korean markings (Jackson, pg. 76, 1979). It carried three each 20 or 23 mm cannons.

A large number of UFO sighting reports are presented in the pages to follow. If these UFO were enemy weapons of war: (1) why would they continue to be used during the truce period? (2) why would the U.S. not be able to identify them more definitively? and (3) why weren’t they used more effectively by the enemy during the actual conflict? There were no UFO reports found which demonstrated clearly hostile intent toward U.S. personnel on the part of the unusual aerial phenomena.

Figure 5

Captured Soviet Made MiG-15

(Reproduced by permission of the National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution)

Military and Political Events:

It is important to have some idea of the major military and political events which took place before and during the Korean Conflict. A number of them are listed in Table 1. It may be significant that the first UFO sighting report was not made until September 1950. It took place 100 miles south of the Yalu River. Twenty two separate sightings occurred after the truce negotiations were underway. This is interesting in light of the fact that open hostilities had ended and yet clearly defined UFO reports continued to come in from observers on the ground and in the sky.

Table 1

Historical Events Surrounding the Korean War (See Key for abbreviations)

________________________________________________________

Historical Background

- Jan. 20, 1945, Harry S. Truman begins Presidency

- July 16, 1945, World’s first Atom bomb detonated near Alamogordo, New Mexico

- Aug. 5, 1945, Atom bomb exploded over the Japanese city of Hiroshima

- Aug. 15, 1945, the Soviet Union takes control of the NK military government until Dec. 26, 1948

- Sept. 8, 1945, USA takes control of SK military government

- March 11, 1948, Key West Agreement (James Forrestal, Secy, of Defense) assembled Joint Chiefs of Staff at Key West to decide “who will do what”

- Early 1949, Soviets withdraw all troops from NK; USA does same from SK except for a small group of military advisors (withdrawn later that year)

- July 1949, President Truman signs the North Atlantic Treaty

- Dec. 22, 1949, Prototype flight of F-86E in Los Angeles

- 1949-1950, NK tries unsuccessfully to take control of SK through insurgency operations

The Civil War Begins

- June 25, 1950, NK army invades SK at nine different points

- June 27, 1950, U.N. declares official sanctions against NK. President Truman orders General MacArthur to use air and naval forces in defense of SK

- June 28, 1950, Seoul (capital of SK) falls to NK invaders

- July 1950, All U.N. forces retreat to a perimeter-defense line about 50 miles around Pusan

- Sept 15, 1950, Amphibious landing made at Inchon. The first contact of U.S. forces of X Corps with NK forces 200 miles north of the NK defensive positions

- Sept 26, 1950, Seoul recaptured

- Oct 20, 1950, U.N. forces move north across the 38th parallel and capture the capital of NK (Pyongyang). Some units move north of the Yalu river, the national boundary between NK and China

- Nov. 1950, Red Chinese army units 850,000 strong, cross into NK to fight against U.N. troops

- Nov. 24, 1950, MacArthur orders an “end-the-war” offensive. A massive Chinese counteroffensive almost immediately cancels this thrust

- Nov. 26, 1950, Red Chinese soldiers cut the escape route of over 200,000 U.N. soldiers and marines who are evacuated by ship from the port of Hungnan

- Dec. 5, 1950, The Chinese hoards sweep south to recapture Pyongyang

- Jan. 4, 1951, The Chinese recapture Seoul in first major offensive

- Feb. 22, 1951, U.N. Command initiates “Operation Killer” along a broad front well south of Seoul and pushes north with superior firepower

- Feb. 1951, Red Chinese make advances in a second major offensive

- March 14, 1951, Seoul is recaptured by U.N. troops

- April 8, 1951, President Truman sends orders relieving Gen. MacArthur of his command. MacArthur had publically advocated direct attacks against the communists in Manchuria, an act considered to be insubordination toward the President and U.S. Congress

- April 21, 1951, Gen. MacArthur leaves FEAF command. Gen. Matthew Ridgway (1895-1971) given command of FEAF

- April-May 1951, Red Chinese mount third major offensive

Attritive Phase of the War Begins

- April 22, 1951, U.N. troops occupy positions just north of the 38th parallel along a line that remained almost constant for the remainder of the war. The battlefield strategy remained to inflict maximum personnel loss along the fixed battlefront and from the air. This approach could not drive the enemy from the field and could never result in total victories, like that achieved in WW2.

- In May 1951, General Van Fleet (Eighth Army Commander) orders a huge coordinated counteroffensive.

- May 9, 1951, the Largest air strike of the war. Over 300 fighters and fighter-bombers attack Sinuiju near the Yalu River.

- July 10, 1951, Truce negotiations begin at Kaesong between U.N. representatives and

Communist commands - Oct 1952, Negotiations break down over one final principle (i.e., prisoners of war should not be returned to their respective armies against their wills)

- Nov. 1, 1952, U.S. explodes its first Hydrogen bomb at Eniwetok Pacific Proving Grounds (Operation Ivy)

- Nov. 4, 1952, Dwight D. Eisenhower elected 34th President of the USA

- Dec. 1953, President-elect Eisenhower visits Korea

- April 1953, Negotiations resume

- July 27, 1953, Truce agreement signed at Panmunjom

- Aug. 1953, Soviet Union explodes a thermonuclear weapon

________________________________________________________

Abbreviations:

SK = South Korea;

NK = North Korea;

The historical events cited in Table 1 are political and military in nature. But what about UFO happenings? There were many other events going on at the same time which should be kept in mind as the war raged in Korea. Some of the more prominent events are listed in Table 2.

________________________________________________________

Table 2

Historical UFO Events

- July 1947, U.S. Air Force begins to study UFO reports seriously after receiving numerous reports by pilots and others in America.

- Sept. 23, 1947, Chief of the Air Technical Intelligence Center (ATIC) prepares a letter to Commanding General of the Air Force stating that it is ATIC’s opinion that UFOs are real and urges that a permanent project be established to study them.

- Jan. 22, 1948, Project Sign (also known as Project Saucer) established at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio.

- Sept 1948, Top Secret “Estimate of the Situation” prepared by ATIC; sent to A.F. Chief of Staff, Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg; returned for more proof; later declassified and burned! (Hall, pg. 106, 1964).

- Feb. 11, 1949, U.S. Air Force UFO Project renamed “Project Grudge“.

- Dec. 27, 1949, Project Grudge final report released; all sightings explained away as delusions, hoaxes, and crackpot reports. The termination of the project is announced.

- Sept. 15, 1951, A Pentagon general requests briefing on Project Grudge findings by Lt. Jerry Cummings and a Lt. Col. from ATIC; orders were given to set up a new study project. Early reports of UFO in Korea very likely figured in this request.

- Sept. 1951, Capt. Edward J. Ruppelt appointed chief of UFO study activity (supported by Lt. Bob Olsson, Lt. Henry Metscher, Lt Andy Flues, and Lt. Kerry Rothstein).

- March 1952, Project Blue Book (code name) officially established at ATIC.

- In April 1952, Life Magazine publishes a major article “Have We, Visitors, from Space?” Hall (1964, pg. 107) suggests it was inspired by several top Air Force officers in the Pentagon. AF Letter 200-5 issued giving Project Blue Book fuller, direct access to pilot (and other) sighting reports.

- July 1952, Newly established Aerial Phenomena Research Organization (APRO) publishes first issue of the APRO Bulletin. Civilian Saucer Investigation (study group) of Los Angeles, California is founded (Jacobs, pg. 84, 1975).

- Aug. 1952, A USAF study of UFO maneuvers begins; emphasis is on the possibility of intelligent UFO control.

- Jan. 14-17, 1953, A.F. (with C.I.A. according to Hall; Ibid.) convenes top scientists to study all available UFO evidence (Robertson Panel). Maj. Dewey Fournet presents evidence and conclusions that UFOs are of interplanetary origin.

- Jan. 17, 1953, Panel concludes its review without it being made public. (Hall notes that “since then, two conflicting versions have been released”).

- Dec. 1953, Joint Chiefs issue “Joint-Army-Navy-Air Force Publication (JANAP) 146” entitled “Canadian United States Communications Instructions for Reporting Vital Intelligence Sightings”

It is very likely that the numerous high-quality U.S. military sightings of UFOs from the

Korean War zone contributed significantly to the continuing Project Blue Book by the U.S. Air Force.

Notes: William Moore presented this astonishing information during the 1987 annual meeting of the Mutual UFO Network held on June 26-28 at The American University, Washington, D.C.

He distributed an eight-page report entitled “Briefing Document: Operation Majestic 12 Prepared for President-Elect Dwight D. Eisenhower: (Eyes Only), 18 November 1952” which allegedly documents this.

First saw action in Korea on July 3, 1950, when an F9F-2 shot down a Mig-15.

First saw action in Korea on July 3, 1950.