by Doug Skinner

Richard Sharpe Shaver died 30 years ago. He was never famous in the usual sense of the word, but the “Shaver Mystery” and the “rock books” were once hot topics in certain circles. That was a long time ago, however, and Shaver ought to be forgotten by now. Surprisingly, he has remained stubbornly alive, and in an unexpected place—the art world. Maybe it’s time to reassess him; maybe we can even clear up a few puzzles and misconceptions.

Shaver’s Early Life

Richard Shaver (he added the “Sharpe” himself later) was born in 1907; he was one of five children. At least two other members of his family were writers: his mother, Grace, was a published poet, and his brother Taylor contributed to Boys’ Life and other magazines. Dick was a smart and bookish boy, surrounded by writers and readers. He grew into a rather restless teen, and had discipline problems in high school. The family moved around a lot; maybe that had something to do with it.

At any rate, by 1930 he was living in Detroit, intent on a career as an artist. He enrolled in the Wicker School, where he also worked as a life model to help meet his tuition. He became a great fan of the muralist Diego Rivera and dabbled in progressive politics; his speech at a Mayday rally that year put his picture in the paper.

The Wicker School eventually fell victim to the crumbling 1930s economy. Shaver married one of his teachers, Sophie Gurivich, and the two soon had a daughter, Evelyn Ann. Postponing his own artistic career, he found work as a spot welder at the Briggs Auto Body Plant.

Shaver had always been somewhat unstable, but now he began to have serious troubles at work. He started hearing voices—at first only when he was welding, then more and more often. His fellow workers’ thoughts rang through his head. Even more disturbingly, he heard underground beings gloating over horrible tortures.

In 1934, Shaver’s brother Taylor died suddenly, of cardiac hypertrophy. The two were close, and Richard took the news hard. He recalled later that he reacted by drinking until he passed out. Only six months later, he was admitted to Detroit Receiving Hospital. He insisted that a demon called Max had killed his brother, and was now after him as well. He was diagnosed as insane, and had to be restrained.

Soon after that, Sophie had him transferred to Ypsilanti State Hospital. He must have responded to treatment, since he was released to visit his parents for Christmas in 1936. It was there that he learned of another tragedy: Sophie had been killed, electrocuted when she moved a heater in the bathtub. Her family took custody of their daughter. Shaver did not return to Ypsilanti.

He was certain now that devils were persecuting him. Over the next few years, he wandered aimlessly and compulsively, trying to shake off the creatures that he believed had killed his wife and brother. He often reminisced about this period later, but his accounts are confused and contradictory; he confessed that he had trouble separating reality from dreams and visions. He tried to stow away in a ship to England; he was imprisoned a few times; he was tormented by giant spiders; he returned to a mental hospital at some point. Max was always after him.

Discovery of the Dero

Later, Shaver would insist that he had discovered an old and jealously guarded secret during this period. Nydia, a blind girl he had seen in dreams and visions, “a form as light in its step as the sea foam that drifted up and touched the beach,” took him down into the ancient network of caverns built by the giant godlike race that had colonized Earth eons ago. There, the halls were still stocked with their “mech,” machines far in advance of our own: telaugs that transmit thoughts, stim rays that amplify sexual pleasure, telesolidographs that beam images through rock. When the sun turned radioactive, these alien Titans escaped. The few that remained devolved into two warring races: the dero, whose brains were so poisoned that they thought backwards and could only do evil; and the tero, who tried to fight the dero and to assist surface men. In the language of the caves, “de” meant “detrimental energy” and “ro” slave: a dero, then, was a slave to destructive impulses. A tero was the opposite, a slave to constructive forces. Max was a typical dero, Nydia a tero.

The details of his story changed at times—Nydia came to him in a Vermont prison, or from a Maryland fishing shack—but his conviction that he had visited the caves never wavered. He always insisted that he had pinched himself when he was there, and that it hurt. He returned to the surface to pick up some of his belongings, and couldn’t find his way back.

Collaborations with Palmer

Shaver was released from the Ionia State Hospital in Michigan in 1943. He went to live with his parents in Barto, a small town in Pennsylvania, and found work as a crane operator. A second marriage foundered after a few months, but his third, to Dorothy Erb, was apparently a happy one. And then he started writing to Ray Palmer.

Palmer, a prolific pulp writer in all genres, had taken over the editorship of Amazing Stories in 1938. Its founder, Hugo Gernsback, had pioneered science fiction—or “scientifiction,” as it was then called—with stories rooted in scientific accuracy and technological prophecy. Palmer slanted the magazine more toward fantasy and adventure. Purists may have preferred Gernsback, but Palmer’s approach proved far more commercial.

Palmer was always looking for new ideas, new writers, and new gimmicks. So when Shaver sent in a key to the meaning of the alphabet, Palmer was willing to try it out. He printed it, and the readers had fun with it, so he asked Shaver for more.

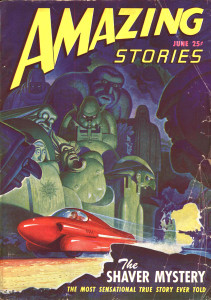

June 1947 issue of Amazing Stories

Shaver responded with stories about the caves and the dero, and Palmer published most of them. Some readers were enthralled, and some enraged, but the controversy was good for sales: circulation increased from 135,000 to 185,000, and Amazing Stories went from a quarterly to a monthly. Palmer called the affair “The Shaver Mystery” and it dominated the magazine from 1945 to 1950.

A number of misconceptions have arisen about those years. Palmer was often accused of perpetrating a hoax by rewriting Shaver’s letters as fiction. In fact, the correspondence between Palmer and Shaver (which Palmer later published) showed that the two men worked together to turn Shaver’s ideas into salable stories. Shaver was a longtime fantasy fan and was happy for a chance to break into a profession that promised more than the 83 cents an hour he made at Bethlehem Steel. His early attempts—particularly the first one, “I Remember Lemuria!”—were thoroughly reworked by Palmer. But Shaver was determined to improve, and collaborated with other writers to polish his output. He conferred with Palmer about style and subject; he even sent sketches of his characters to the art director. And he wrote non-cave stories as well: fantasy and adventure yarns for Fantastic, Mammoth Adventure, and the other pulps that Palmer also edited for the same publishing house, Ziff-Davis.

Shaver’s main literary model was Abraham Merritt. Merritt isn’t read much today, but his fantasy novels were quite popular throughout the ’20s and ’30s. Beginning with The Moon Pool in 1919, he produced a series of novels about underground caverns, lost races, ancient ray machines, shell-shaped hovercraft, and other marvels. He was also a member of the original Fortean Society and the editor of The American Weekly, a Sunday newspaper supplement that often featured scientific and historical oddities. Shaver thought Merritt had seen the caves but could only mention them in fiction. One might also suspect that Merritt’s novels had influenced Shaver’s beliefs.

Shaver was serious about his mission: the dero were ruining our lives and needed to be exposed. Palmer was not convinced, but he was intrigued by Shaver’s unorthodox scientific ideas, wild imagination, and ingenious interpretations of mythology. He didn’t question that Shaver had seen strange things, but thought that the caves were probably astral or ethereal rather than physical. To Shaver, a staunch materialist, this was “dero wool.”

Thousands of readers wrote in with their own experiences, and Palmer liked to cite them as evidence for Shaver’s claims. This too has been misunderstood. Many letters did describe caves and dero—some of which, I suspect, were written by Palmer himself. But Palmer lumped all Fortean, paranormal, and psychic subjects into the Shaver Mystery; it could all, somehow, be connected to Shaver.

The Birth of Fate

After a few years of this, Amazing Stories became primarily a forum for these subjects. There weren’t many alternatives back then, except for a few privately circulated newsletters. Palmer had stumbled onto an unexpected audience.

The Mystery peaked in June 1947, with a special issue loaded with Shaver stories and essays—and a Vincent Gaddis article on spaceship sightings that presaged the flying saucer craze that was soon to follow. In fact, when Kenneth Arnold’s sighting made news that month, both Shaver and Palmer saw it as further proof of the caves. After all, Shaver’s stories had long sported spacecraft, and Palmer had been writing editorials about alien visitors and government cover-ups since 1946.

By this time, many readers—and, more critically, Messrs. Ziff and Davis—were getting tired of Shaver. He couldn’t prove his claims, and the stories were getting repetitive. Many were also alarmed by Shaver’s unbridled sexuality—Palmer once had to snip out a 50-page bedroom scene. Shaver agreed to stick to straight-ahead fiction, and the dero were confined to The Shaver Mystery Magazine, a smaller magazine he started with one of his collaborators, Chester Geier.

Meanwhile, Palmer and another Ziff-Davis editor, Curtis Fuller, had founded a new digest to cater to this newfound audience for the paranormal. They called it Fate, and it did so well that Palmer quit Ziff-Davis to devote himself to it. For some reason, he edited it under the name of Robert N. Webster. Despite regular ads for the book edition of I Remember Lemuria, Shaver was never featured in it. A 1950 article on him was not well received—one irate subscriber called it “entertainment for morons.”

Fate, though, wasn’t quite what Palmer was after. Within a few years, he left to start his own line of magazines: Mystic (later Search), Other Worlds, Flying Saucers, Space World—many of which changed titles and formats erratically. Shaver wrote for several of them. Despite spiraling costs and poor health, Palmer kept his creations afloat, even when he had to print them on remaindered paper and could no longer afford to pay contributors.

The new editor of Amazing Stories, Howard Browne, didn’t like Shaver’s work—he once called it “the sickest crap I’d run across.” With that outlet gone, Shaver’s writing career declined. He sold a few pieces to other magazines (like If), but mostly appeared in fanzines and Palmer publications. UFO buffs did their best to keep the Mystery alive; the idea that the saucers came from underground was popular in UFO publications and became a regular subject on Long John Nebel’s nightly radio talk show. Still, Shaver wasn’t selling many stories. He suffered from depression and took to spending long hours in the bathtub.

Rock Pictures

Sometime in the ’50s, however, he made a discovery that came to dominate his life. One day, his wife dumped a handful of stones on his desk, remarking that they seemed to have pictures on them. After studying them, he decided that they weren’t just stones, but the books of an ancient race of sea people. He had found the evidence that had always eluded him: physical proof of the elder races.

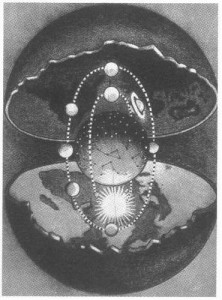

These rocks, Shaver believed, were the records of the giant mermaids and mermen who had developed a rich civilization eons ago, before the moon fell and bounced off the earth. They made books by projecting images into rock as it hardened. These images were complex and variable; there were pictures that changed from different perspectives, and pictures under and inside one another. Shaver concluded that these “rock books” must have been projected, like movie film, by some long-lost machine.

Shaver worked tirelessly to publicize his rocks. He photographed them, wrote about them, and tried to sell them through the mail. He made very few converts.

Eventually, Shaver turned to painting to show the pictures that nobody else seemed able to see. His method was somewhat unusual. A sheet of cardboard or plywood was first coated with a variety of chemicals, chosen to simulate the texture of rock and to “respond easily to the minute light forces.” Shaver had no set mixture, but experimented with different combinations of laundry soap, wax, Windex, glue flakes, dye, and diluted paint. He also tried fixative, but abandoned it when Dorothy complained about the smell. A rock was then sawed open and set on an opaque projector. Once the image was focused onto the cardboard, he sprinkled water over it and gave the picture time to form. Only then did he get out his paints to carefully touch it up clarify it.

The resulting paintings were fluid and hallucinatory: distorted dream-like visions of faces, battles, mermaids, and strange creatures. And, always, naked women. “Oh yes, they were sexy, these voluptuous ancient sea people!” Shaver explained. He insisted that the paintings weren’t his own creations, but strictly documentation.

The mythical realms of Agartha and Shambala

Shaver devoted most of his later life to painting and to promoting the rock books. Palmer published a hardcover book, The Secret World, that preserved many of the paintings and rock photos (as well as an installment of Palmer’s memoirs), and a 16-volume series, The Hidden World, that collected both early and late Shaveriana. Palmer also revealed in an interview that Shaver had been confined to a mental hospital for much of the time that he claimed to have spent in the caves, which didn’t help either of their reputations. Shaver himself planned a long treatise on the rocks, The Layman’s Atlantis; he printed a few chapters as booklets in 1970.

Reborn as Outsider Artist

Shaver’s writings have been largely ignored since his death. Many of them, I would suggest, deserve a better fate. Some are just standard space opera, but others are not quite like anything else in literature. “Erdis Cliff” (Amazing Stories, September 1949), for example, manages to combine heretical physics, a talking purple pig, atheism, Greek mythology, excerpts from the channeled Bible OAHSPE, and an orgy led by Satan—who, we learn, is actually a harmless but lusty cave alien. Nor, for that matter, is there anything quite like the disturbing and hallucinatory memoir “The Dream-Makers” (Fantastic, July 1958). I also enjoy Shaver’s articles for Palmer’s Forum, which treat environmental and social issues from Shaver’s own soulful, quirky perspective.

Shaver’s rock art, however, has found a wider audience. Brian Tucker organized an exhibit at the California Institute of the Arts in 1989, and at Chapman University in Orange, California, in 2002. The LA Weekly wrote about the latter show that Shaver’s work “ranks with the Surrealist paintings of Max Ernst and Jean Dubuffet.” Shaver’s work has also been shown at the Curt Marcus Gallery in New York City in 1989 and at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco in 2004. Norman Brosterman exhibited some of his collection at the Christine Burgin Art Gallery and at the Outsider Art Fair in New York City. Rock photos have been published in recent issues of Cabinet and The Ganzfeld.

Posterity will have to decide whether Shaver’s art is to be remembered. I can only add that I have one of his paintings, and like looking at it. Meanwhile, some of Shaver’s fans continue to keep his memory alive—particularly Jim Pobst (to whom I’m indebted for his research into Shaver’s early years) and Richard Toronto, whose indispensable website can be found at www.shavertron.com.

Our Own Worst Enemies

There’s a hidden message in Shaver’s work, one that’s often overlooked by both enthusiasts and detractors. Quite simply: We are the dero.

To Shaver, we have virtually unlimited potential. Within us is a huge untapped capacity for wisdom, strength, vitality, and beauty. We could be like gods. Instead, we’re a stunted, perverted bunch: we kill one another, poison our planet, stultify ourselves with mindless jobs, cut down forests to put up ugly boxlike cities, vilify intelligence, and condemn sexuality. We think backwards and embrace everything that’s vile, nasty, and foolish.

Shaver may have been overly optimistic about our capabilities, but he did have a point. We can do better. And if it takes a Shaver revival to get that into our little dero heads, we might as well have one.

Doug Skinner is a Fortean writer/artist/ and Off-Broadway (with Bill Irwin) performer in The Amazing Stories of Richard Shaver.